Who should be in charge of the cabin crew on the short flight to Prague? Before the plane had even begun to move from its Heathrow boarding spot, I distinctly heard the captain announce the name of my friend. I sent word. Soon afterwards, the friend rushed up, sat herself in the vacant next seat and gave me a cuddle. Then, all at once, she leapt up again for the take-off. Shortly thereafter, little bottles of champagne began to arrive.

Wandering the streets of Prague I was struck, as I had been in the minibus from the airport, by the large, unrebuked graffiti everywhere. In Václavské Námestí (Wenceslas Square), amid all the usual male crewcuts, there were numerous much more criminal types. I was accosted twice by people begging, once by an English-speaking girl who asked ten crowns “to get home”. This threw me into great confusion, as I was still shaky over the money. I gave her all my change but then worried that this was worth practically nothing. (She had been asking for only 20p in English money, scarcely enough to buy a few sweets for a child.)

The communist hell is still visible: dirt, poverty, begging, crime. At the southern end of the Square, a “memorial to the victims of communism” is like a wound, with fresh flowers, unofficial, small, still resented, no doubt, by all those nostalgic for the days of order and discipline.

It was difficult, in spite of many instructions, to find a Post Office to send off to my friend Šárka a copy of my book of poems. Happily, the building on the corner was the British Council – no less. Here a Čzech woman with excellent English drew a little map for me to find, not only the Post Office, but also the Globe bookshop-café. The Prague Writers Festival, she told me with a gesture towards a poster on the wall, was just getting under way during the week of my visit. Her efforts continued and soon two free tickets and a spare programme were produced, the latter a substantial booklet with biographies and excerpts in English translation.

This is a stroke of heaven. Everything seems to be very near here, so it will require little effort, and less of my ample enthusiasm, to get over to the Ypsilon Studio this afternoon.

Finished, alas, with Anthony Burgess’s Earthly Powers, the wrath of God and the revenge of Satan locked in close combat, blade to barbed blade. Innocent souls spun to destruction in the backwash of a saint.

The lady at the British Council was rewarded, to her delight, by flowers and some poems. I went on early to the Ypsilon Studio and wandered into the heart of this former cinema in which Communist officials used to allow themselves to watch banned foreign films, down spirals of steps, and was offered a free coffee by a lady at a hatch. Leaning elegantly nearby was a man who introduced himself as Petr. His excellent English enabled him to tell me about this Art Deco building and about the previous evening’s event. Three American authors – Susan Sontag, William Styron and Robert Stone – had packed the theatre and shocked, among others Petr himself, by how honestly they expressed themselves. Čzechs, Petr explained, had been brought up under communism to respond in uniformity, to “have no fantasy”. An art lesson at school was one in which children all drew the same thing: a Russian flag alongside a Čzech flag. The large audience had all come to learn something about individualism and had not been disappointed.

The day’s programme was Greek and the discussion, when it started, was excellent. But I was moved most by the single poet, Katerina Anghelaki-Rooke. Sixty years old, quite disabled by some deforming condition, she read poems in Greek that, in their accompanying English translation, seemed to grow and fill the hall, tall vibrating columns of pity and terror, their purity and concentration immense.

Later, when I had managed to buy a copy of the excellent English translations, I approached the poet to sign them. Gradually she manoeuvred the vacant chair next to her to rest the book on: “I am a table person.” Then she wrote away, asking my name. I crouched beside her.

“Do you write?” she asked.

“Yes, I’m a poet,” I said.

She looked up. “Why do you say it so sadly?” she asked with her wide smile. Reaching out, she affectionately brushed my cheek with her hand.

Only when I walked shortly afterwards to the Globe literary café for a signing by these authors, did the immensity of this sink in. Passing me just inside the Globe, Katerina saw me again.

“I feel I have known you all my life,” she said.

I replied, “You touched my soul just now.”

By now dazed with sadness and happiness simultaneously, I sat by the books while she read another poem in English, following in my copy. Later I offered to buy Katerina a meal in the interior of the café and she consented, though in the event she wanted only a beer. We roamed widely, in spite of regular interruptions by Greeks, one worried that she had separated from the party, another to give her a signed copy of his book. Occasionally she became excited and shouted loudly. She had just completed translating into Greek the whole of Eugene Onegin and spoke of Pushkin’s language (she knows Russian). Cavafis’ homosexuality was a factor in his Anglophone popularity. English, language of generals and empire, was a language of concealment, perhaps the secret of its political success. Because of a lack of gender agreement, an entire love poem could remain ambiguous as to whether the beloved was a boy or a girl. Rilke she adored, bringing her fingertips to her lips in a kiss. And much else, much else.

I said, quoting from her ‘Red Moon’ that the reason that I was sad was that

All the poems I had ever heard

[Had] returned from afar to bury me.

When I alluded to the ending of ‘Yanoussa counts her possessions’,

Forty-nine and the obsession over

she said that, with men, it goes on a bit longer.

“I am fifty-two,” I said.

“…and the obsession’s still going!” she quipped. We both roared with laughter.

I was most interested in the Čzech writers. Their first event involved four younger Čzech writers reading from their work, translated by Jim Naughton of St Edmund Hall, Oxford University. Only one, Petr Borkovec, was a poet. I had become frustrated in the programme booklet by the, admittedly skilful, English translation by Justin Quinn, who had managed to reproduce elements of the form, such as the rhyme scheme. Nevertheless I felt the poem itself hovered somewhere behind the English translation. In the Globe once more, I introduced myself to Petr and Jim and, at the table there and then, spontaneously, began to work out with them a literal version. The poetry of Borkovec had, for me, reminiscences of the still-life quality of Osip Mandelstam’s earliest volume, Kamen (Stone).

Eventually, back in England, I continued with our efforts at retranslation, with the following result:

The lyre is weightless. Overnight,

October has collapsed onto the platform.

The electrified train grates – the station is gone.

Fifteen minutes conveys the travelling scene

to a halt whose beauty chills.

Green clouds, a poplar in blue shade,

a field at the edge of town – Arles for an instant.

And when the low tea-coloured sun collides

with the margin of the town in windows,

I catch sight of a Bethlehem crib.

The lyre is light, so I search for it

as for a wallet or lost ticket.

The younger Čzech prose writers who read from their work seemed to have in common a vein of fantasy, even surrealism. While this was occasionally breathtakingly funny, it seemed to display itself tantalisingly in front of an audience with which it did not connect. Those I spoke to afterwards, Čzech and English, were not impressed. Perhaps surrealism remains the most difficult current to integrate in the modern literary stream, the unconscious being very resistant to our attentions.

The subsequent event was a single author, Josef Švorecky. Breathless with an incipient cough-cold, he read, first in Čzech then in English, a piece concerned, like so much of his work, with jazz, but in this one he improvised a blues to a woman. All poetry worthy of the name, he said, originates in this feeling between a man and a woman. (Subsequently every effort of mine to locate the source of this reading has failed.)

In spite of such passional grounding for his work, Švorecky was decidedly modest, even self-effacing. What was striking to the visitor was the open affection in which he is held by his young Čzech audience. One questioner wondered why he was such a good person. Why indeed? Švorecky did not know but was clearly pleased.

There can be no doubt that there is abroad here a Spirit of 68. While it does my heart good to hear Bob Dylan and Janis Joplin playing at the Globe, what can it all mean to the younger generation? Do they really want to tear up paving stones and throw them at the police? Perhaps all of this is the achievement of a delicate posture. In the Old Town there is a Marquis de Sade café, into which I peeped one afternoon, finding the roomy wooden interior, with benches, tables and mirrors to relieve the gloom, very inviting. But if one was to read out, suitably translated, a few paragraphs of the Marquis to the customers, the place would quickly empty.

It is the innocence of childhood, the post-communist lull of potential. Some of the Festival presenters, with flower-wielding fixed smiles, seem to think this is all a celebration of awareness, with words and gestures to suit, a happening, a flowering of new consciousness. One strikingly tall philosophy student at Karlovy University I spoke to about poetry had read only Lawrence Ferlinghetti.

Many Čzechs wish to attach their country like a cattle tick to the belly of America. Growing up in Britain one is shielded, to an extent, from the world-wide adoration of America. Indeed I spend much of my time defending the poor things.

I had experienced a tingle of shock, close to Václavské Námestí by one of the little kiosks advertising organised tours: Terezín. The name held sweet horror. A tourist destination? But gradually it came to seem to me a duty to go, a quiet pilgrim journey amid the Festival flowerings. When would I again be in central Europe within range of a concentration camp? So early one morning a guide came to the hotel to collect me and walked me to the minibus. This tall young Karlovy student was changing his course to one in statistics. He had done some very boring work, he told me, for Reuters, as a result of which he had discovered “I am not a machine” and become altogether averse to computers.

A British couple, who quickly brought to mind the Borrowers, got into the minibus to wait but, claustrophobic, got out again. The wife endlessly berated everyone in complaint but, when her husband joined in loyally, she said:

“Now, keep calm. You must keep calm!”

Later, at the Terezín crematorium he placed a little Yarmulke on his head, so much of this behaviour would have been anxiety.

Our guide, a woman with arthritic hands in her late fifties and an ex-journalist, gave a rich and insightful commentary. However she was also pessimistic and embittered, for instance at the failures of the post-Communist governments:

“We do not have real democracy in this country.”

I appreciate the intensity of these concerns; but like my Russian friends, people here do not seem to appreciate that democracy means boredom. The Russians certainly think it means the continuation of apocalypse by other means. In Britain we have been asking whether university students should receive grants or pay tuition fees. Ah, that such a throbbing domestic issue should attend the rebirth of the Scottish parliament!

Parliamentary democracy is an admirably labour-intensive source of occupation for those with second rate talents. Let them harmlessly manage and administer our affairs, while those capable of thinking, creating and discovering get on with their work undisturbed. Surely this state of affairs is to be preferred to that in Plato’s Republic, where philosophers are compelled to set aside philosophy, against their will, and rule.

Terezín was a moving, but not a shocking or new, experience. My education seems to have included a great deal of the Holocaust. One could see that families were kept together (as they were not in black slavery), and that prisoners were fed. Matters compared favourably with, say, conditions in the Gulags. Indeed a typical Terezín barracks was strongly reminiscent of actual conditions today in the Saint Petersburg prison we visited in 1991.

Terezín was essentially a transit camp and Gestapo prison under the Nazis and the cultured Jews of the Ghetto poured forth music, writing and art, notably the sketches of Fleischmann, preserved on display in the Museum of the Terezín Ghetto, whose every caption begins, “People …” Stark, haunted and guilt-dirty as it is today, with its millions of sordid bricks, its quietness effectively conceals, what Fleischmann’s sketches reveal, that the place was a pullulating mass of human beings, some 60,000 at any time. This is truly difficult to imagine.

Given their limited resources, the authorities, Communist and post-Communist, have done well to keep the place alive as a meaningful memorial. But little Israeli flags stuck in water-pipes, occasional wreaths and witnessing candles, can never cover over, can never make more than a patchwork of fabric fragments of, the grief, indignation, preservation of children’s names. This is the best we humans can do to tame and domesticate, as a member of the historical order, this outbreak of rationalistic horror. (Our guide revolved the dilemma of “good Germans, bad Germans”.) We draw the fragments together, piecemeal, but they can never form a whole, finished garment. The facts of rational blackness keep erupting; the grief goes on; the memorial is provisional.

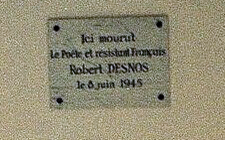

There is, at Terezín, a memorial to the French poet and resistance hero, Robert Desnos. A last poem of his was sent to his wife Youki by a Polish student who found the poet dying of typhus among survivors in 1945:

Last Poem

I have so fiercely dreamed of you

And walked so far and spoken of you so,

Loved a shade of you so hard

That now I’ve no more left of you.

I’m left to be a shade among the shades

A hundred times more shade than shade

To be shade cast time and time again into your sun-transfigured life.

Back at the Festival, I now had to bid a fond farewell to Katerina Anghelaki-Rooke. She was soon flying home to Greece and Aegean sunlight. We had both been amused at the antics of photographers and I read her in draft the little joke poem I had composed on this subject:

Photographers

They clamber over each other at the foot

of the stage, their jaws snapping,

the FAMU girls, beautiful and determined, their hair

between copper and burgundy, firing the season’s black,

the men lean, muscular, with heads forcefully crewcut.

The oversize lenses lurk like bins

to be fed with light.

And all this for writers?

But such expected adorations are ignored.

The mind of a writer is like a defunct wasps’ nest:

thousands of empty chambers rustle

in the small breeze of a thought,

a faint susurrus of indifference

to the crocodiles far below.

The concierge at my hotel, a young man, perhaps like so many a student himself, made a request. His girlfriend, a student of English, would like me to give her, autographed, some of my poems. Martiná, she had the same name as me. I found three poems that had accompanied me by accident, which he duly photocopied. I signed and wrote the same message on each one for her.

“Tell her,” I said, “that normally I wouldn’t write the same thing three times over, but I have spent the morning in a concentration camp.” He twinkled.

I, in whom these tides sometimes so majestically and impetuously rise, yesterday failed three tests of practical love.

- When there was no group collection for our guide, I failed to add my two-penn’orth to the other individual contributions.

- When a lady in the crematorium (only dead bodies were burned here, many Israeli flags notwithstanding) offered a memorial candle for sale, I failed to buy and light one.

- When a copper-haired girl, who had gladdened my boyish heart by accepting my invitation to dinner, told me she now couldn’t make it because her “boyfriend is very angry”, I failed to sympathise with the problem this had created for her.

Nevertheless, wandering in the Old Town today, I was given three chances in quick succession to redeem myself, all of which I took, in the form of Romanian, or perhaps Kosovan, refugee beggars. In the matter of begging, though loath to be parted from my money, I hold to the view of Samuel Johnson:

Why should the poor be denied such sweeteners of their existence? Life is a pill which none of us can bear to swallow without gilding. I give money to beggars to enable them to beg on. It is sufficient that our brother is in want: by what way he brought his want upon him let us not too curiously enquire.

He didn’t care, in other words, whether the recipient was worthy or unworthy, or whether he or she spent the money on drink. In this, I believe, he was adhering to the teachings of Jesus, who always urged generosity in alms – unqualified giving.

There is something in the craft and habit of begging that approaches a theatre of abjection. The posture, yesterday, even of a mother holding a one year old child, was one of profound stooping, so that, bent double, her face almost touched the ground and one wondered if she had fallen asleep.

Of course, there arises in the minds of passers-by an intolerance of this abjection, expressed in comments that can readily and repeatedly be overheard by anyone who cares to spend ten minutes standing close to a beggar. They’ll spend it on drink … She’ll go home in a taxi … He probably owns three houses. There is something about the presentation of an opportunity for charity that arouses antipathy.

Nevertheless the beggars accentuate and exaggerate all the more their postures of abjection, so that the whole performance, including the inflamed responses of passers-by, comes to seem a special form of theatre.

At the Festival, Ian McEwan had arrived in excellent form but, delighted with his audience, got increasingly into his stride and imperturbably delivered himself, in interview, of immaculate impromptu paragraphs that needed no revision at all. He was particularly funny about the interview mode itself, a genre that began with the Paris Review, and now makes it imperative that a writer explain him- or herself constantly to journalists.

He described the American circuit of literary readings, how polite and friendly everyone was, and how, alone in the elevator, he would pull wild, evil faces but, stepping out at the bottom, put on again the wide-smile, pleased-to-meet-you mask.

People are not, he said, in search of any specific information. They just want to stroke the writers gently with the palms of their hands. Like a children’s farm, put in Jim Naughton, bilingual mediator of this discussion. Yes, said McEwan, but as with children’s farms, there are fears about E. Coli. It may not always be a safe thing to do, to stroke a writer.

McEwan was particularly good on empathy. Cruelty occurs, he observed, when there is no bond of empathy between oppressor and victim. One does not put oneself in the place of the other. In this sense, the novel is an inherently moral form, as it sets out to imagine the feelings and experiences of other people.

One day, in the Globe where so many things can happen so easily, a young woman squeezed past my table to enquire whether the seats behind were occupied. No-one had sat in either of them for half an hour, I said. She duly sat herself down. Immediately a couple reappeared and, on the basis of a discarded newspaper and an empty coffee-cup, claimed the seats as their own. Gesturing to an empty seat at my table, at which I had been peacefully writing, I encouraged the woman to squeeze under the stairs and sit down there.

One day, in the Globe where so many things can happen so easily, a young woman squeezed past my table to enquire whether the seats behind were occupied. No-one had sat in either of them for half an hour, I said. She duly sat herself down. Immediately a couple reappeared and, on the basis of a discarded newspaper and an empty coffee-cup, claimed the seats as their own. Gesturing to an empty seat at my table, at which I had been peacefully writing, I encouraged the woman to squeeze under the stairs and sit down there.

“They had not sat there for half an hour, “ I repeated.

“Oh I believe you,” said the woman. She ordered a beer. I resumed my rapt concentration.

After a while a conversation easily started up. It easily took little turns, winding here and there. I could not remember making an acquaintance before in such uncomplicated fashion. We spoke English, we understood each other, we saw life through the same eyes. After a while, in the same straightforward way, she told me that last year, only a few metres from her house, she had been attacked late at night and raped, suffering extensive brain injuries. Ever since, she had experienced constant fatigue and “brain fog”. For ten minutes I sat speechless, trying not to let the tears roll down my cheeks. Such a brilliant, frail creature.

Wandering around the streets of the Old Town, I eventually succeeded in buying some small presents. In a literary café in Tynska Street, I was joined at my table by a young couple. The girl was persistently giving the boy a hard time. Nothing he could say proved acceptable. This was apparent, even to one ignorant of the language, in the rhythms of the Čzech, though these were not overly quarrelsome.

Eventually I asked in English:

“Are you happy today?”

So-so, she see-sawed her thumb and little finger.

“How did he upset you?” I asked.

Dismayed, she replied, “He speaks English too!” as if the premise had been a separate dialogue. “It’s just normal argue,” she said. I left them with a smile.

In a bookshop in a nearby square, I spoke with a girl who seemed able to answer every question and to guide my discovery of Čzech authors. Had she read every book in the shop? It seemed so. There must be stupid Čzechs, but their mothers seem to stifle them in the cradle at an early stage, so that it is impossible to come across them later on. Prague is a city in which everyone reads. But she was from Central Asia, she said, had lived in Saint Petersburg and would move next year to Spain. Then how had she learned such excellent English? “I picked it up along the way.”

In a bookshop in a nearby square, I spoke with a girl who seemed able to answer every question and to guide my discovery of Čzech authors. Had she read every book in the shop? It seemed so. There must be stupid Čzechs, but their mothers seem to stifle them in the cradle at an early stage, so that it is impossible to come across them later on. Prague is a city in which everyone reads. But she was from Central Asia, she said, had lived in Saint Petersburg and would move next year to Spain. Then how had she learned such excellent English? “I picked it up along the way.”

Girl in a Prague Bookshop

Who is not looking for love? Your lungs crave to be packed like a barrel with smoke, even as your fingertips tap out a path through new Czech writing. Who says it’s a strain, being someone, belonging somewhere? Intelligence senses itself in others. You refuse one of those invitations that so easily give rise to regrets. The best intentions are full of bacteria. I am no businessman, but voyage through people and pages. I look at people’s faces as lovingly as at their whole bodies, searching out the soul that, sometimes, leaps out unsearched.

You say being a woman is normal, but I watch the days flow back. I have pleaded with stupid people and mourned the treachery of objects. We bob, laced in a seaweed web. Like any woman you dazzle me with my own longing. |

Twisted Spoon Press, she told me, was a one-man-band publisher of experimental and innovative writing. Wishing to support this, I brought over to her desk all six or so titles from the shelf.

“Which one should I buy?”

“Oh,” she rose to the challenge, frowning, “It would be either this one or this.” She brought forward two titles from the pack. I replaced the others.

“Now, which of these two?” I continued.

She now demurred. “You should open it and read any paragraph, to see what it is like,” she said.

“I have done that,” I said, “with this one”, indicating a grey cover. “And I was … scared.”

“Modern literature is getting so depressing,” she said.

“It always was,” I replied. We laughed. I started to indicate a preference for the other, rose-covered book.

“But this one is very interesting, I think.” The grey again.

“You want me to be brave,” I concluded, settling for her preference, Lukáš Tomin’s Kye.

Like all young people in Prague she soon needed to go the doorway for a long gulp of smoke. My ‘Snow’ poems, a tribute to Boris Pasternak, were included in New Writing 7, I told her, perhaps the only work of mine available in Prague. I don’t know whether she looked at it after I left.

She had to serve all day in the shop, and I had an evening engagement, so we weren’t able to meet for a meal to talk further. So many things I wanted to ask her, that perhaps she would not have wished to answer…

Sunday morning and the Prague Post enables me to find an Orthodox church, Ss Kyril and Methodius, apostles to the Slavs, at the corner of Na Zderaze and Resslova. I believe this is the building where some Čzech assassins of a German general in the war, betrayed, shot themselves rather than face capture. The Nazis had wanted to flood the crypt where they were hiding.

Sunday morning and the Prague Post enables me to find an Orthodox church, Ss Kyril and Methodius, apostles to the Slavs, at the corner of Na Zderaze and Resslova. I believe this is the building where some Čzech assassins of a German general in the war, betrayed, shot themselves rather than face capture. The Nazis had wanted to flood the crypt where they were hiding.

I feel readily at home. Afterwards, in the Orthodox tradition, there is virtually no social contact, but I buy two tiny icons. One of them, a Virgin and Child, I later give to my friend with “brain fog”.

And so home, to rainy, neglected England. Why do I not like the self I am in England? A cheque from Faber awaits me for £23, being the proceeds from individual viewings of my poems over the internet. This is definitely a first.

I had accepted a P & O freebie to look over their super new cruise liner, the Aurora, in Southampton. This was impressive but a deeply disagreeable impression was created by all the members of the public crawling, like me, all over it. Some had boarded and gone straight to one of the restaurants for tea and cakes. For many, to queue to inspect the luxury of the penthouse suite was the culmination of their life’s aspirations. It may be true, as de Tocqueville said, that consumer democracy keeps people in a state of permanent childhood.

O Prague remember me! Keep alive the Spirit of ’68!

22nd April 2000

Katerina Anghelaki-Rooke, From Purple Into Night. Translated by Katerina Anghelaki-Rooke and Jackie Willcox. Beeston, Nottingham: Shoestring Press, 1997.

Petr Borkovec, untitled poem from Polní práce (Field Work, 1995), tr. Jim Naughton and Martin Turner.

Robert Desnos tr. XJ Kennedy. In Modern European Poetry. ed. Barnstone, W., Terry, P., Wensinger, A.S., Friar, K., Raiziss, S., de Palchi, A., Reavey, G. and Flores, A. New York: Bantam Books, 1966.

Samuel Johnson, on alms being applied by their recipients to spirituous liquors. From the 1984 BBC Radio 3 ‘Kaleidoscope’ centenary documentary drama feature on Johnson.

Martin Turner, ‘Snow.’ In Callil, C. and Raine, C. (eds) New Writing 7. London: Random House Vintage /British Council, 1998.