May 2008

Monthly Archive

May 31, 2008

Posted by mvlturner under

Travels | Tags:

Anthony Burgess,

begging,

Boris Pasternak,

Borkovec,

British Council,

Cavafis,

Cavafy,

de Tocqueville,

Earthly Powers,

Eugene Onegin,

Fleischmann,

Globe Café,

Ian McEwan,

Jim Naughton,

Josef Švorecky,

Kamen,

Karlovy University,

Katerina Anghelaki-Rooke,

Kye,

Lawrence Ferlinghetti,

Lukáš Tomin,

Marquis de Sade café,

memorial to the victims of communism,

Museum of the Terezín Ghetto,

Osip Mandelstam,

Paris Review,

Prague Post,

Pushkin,

Rilke,

Robert Desnos,

Robert Stone,

Russian democracy,

Samuel Johnson,

Ss Kyril and Methodius,

St Petersburg,

Susan Sontag,

Svorecky,

Terezín,

Theresianstadt,

Twisted Spoon Press,

Tynska Street,

Václavské Námestí,

Wenceslas Square,

William Styron,

Ypsilon Studio |

Leave a Comment

Who should be in charge of the cabin crew on the short flight to Prague? Before the plane had even begun to move from its Heathrow boarding spot, I distinctly heard the captain announce the name of my friend. I sent word. Soon afterwards, the friend rushed up, sat herself in the vacant next seat and gave me a cuddle. Then, all at once, she leapt up again for the take-off. Shortly thereafter, little bottles of champagne began to arrive.

Wandering the streets of Prague I was struck, as I had been in the minibus from the airport, by the large, unrebuked graffiti everywhere. In Václavské Námestí (Wenceslas Square), amid all the usual male crewcuts, there were numerous much more criminal types. I was accosted twice by people begging, once by an English-speaking girl who asked ten crowns “to get home”. This threw me into great confusion, as I was still shaky over the money. I gave her all my change but then worried that this was worth practically nothing. (She had been asking for only 20p in English money, scarcely enough to buy a few sweets for a child.)

The communist hell is still visible: dirt, poverty, begging, crime. At the southern end of the Square, a “memorial to the victims of communism” is like a wound, with fresh flowers, unofficial, small, still resented, no doubt, by all those nostalgic for the days of order and discipline.

It was difficult, in spite of many instructions, to find a Post Office to send off to my friend Šárka a copy of my book of poems. Happily, the building on the corner was the British Council – no less. Here a Čzech woman with excellent English drew a little map for me to find, not only the Post Office, but also the Globe bookshop-café. The Prague Writers Festival, she told me with a gesture towards a poster on the wall, was just getting under way during the week of my visit. Her efforts continued and soon two free tickets and a spare programme were produced, the latter a substantial booklet with biographies and excerpts in English translation.

This is a stroke of heaven. Everything seems to be very near here, so it will require little effort, and less of my ample enthusiasm, to get over to the Ypsilon Studio this afternoon.

Finished, alas, with Anthony Burgess’s Earthly Powers, the wrath of God and the revenge of Satan locked in close combat, blade to barbed blade. Innocent souls spun to destruction in the backwash of a saint.

The lady at the British Council was rewarded, to her delight, by flowers and some poems. I went on early to the Ypsilon Studio and wandered into the heart of this former cinema in which Communist officials used to allow themselves to watch banned foreign films, down spirals of steps, and was offered a free coffee by a lady at a hatch. Leaning elegantly nearby was a man who introduced himself as Petr. His excellent English enabled him to tell me about this Art Deco building and about the previous evening’s event. Three American authors – Susan Sontag, William Styron and Robert Stone – had packed the theatre and shocked, among others Petr himself, by how honestly they expressed themselves. Čzechs, Petr explained, had been brought up under communism to respond in uniformity, to “have no fantasy”. An art lesson at school was one in which children all drew the same thing: a Russian flag alongside a Čzech flag. The large audience had all come to learn something about individualism and had not been disappointed.

The day’s programme was Greek and the discussion, when it started, was excellent. But I was moved most by the single poet, Katerina Anghelaki-Rooke. Sixty years old, quite disabled by some deforming condition, she read poems in Greek that, in their accompanying English translation, seemed to grow and fill the hall, tall vibrating columns of pity and terror, their purity and concentration immense.

Later, when I had managed to buy a copy of the excellent English translations, I approached the poet to sign them. Gradually she manoeuvred the vacant chair next to her to rest the book on: “I am a table person.” Then she wrote away, asking my name. I crouched beside her.

“Do you write?” she asked.

“Yes, I’m a poet,” I said.

She looked up. “Why do you say it so sadly?” she asked with her wide smile. Reaching out, she affectionately brushed my cheek with her hand.

Only when I walked shortly afterwards to the Globe literary café for a signing by these authors, did the immensity of this sink in. Passing me just inside the Globe, Katerina saw me again.

“I feel I have known you all my life,” she said.

I replied, “You touched my soul just now.”

By now dazed with sadness and happiness simultaneously, I sat by the books while she read another poem in English, following in my copy. Later I offered to buy Katerina a meal in the interior of the café and she consented, though in the event she wanted only a beer. We roamed widely, in spite of regular interruptions by Greeks, one worried that she had separated from the party, another to give her a signed copy of his book. Occasionally she became excited and shouted loudly. She had just completed translating into Greek the whole of Eugene Onegin and spoke of Pushkin’s language (she knows Russian). Cavafis’ homosexuality was a factor in his Anglophone popularity. English, language of generals and empire, was a language of concealment, perhaps the secret of its political success. Because of a lack of gender agreement, an entire love poem could remain ambiguous as to whether the beloved was a boy or a girl. Rilke she adored, bringing her fingertips to her lips in a kiss. And much else, much else.

I said, quoting from her ‘Red Moon’ that the reason that I was sad was that

All the poems I had ever heard

[Had] returned from afar to bury me.

When I alluded to the ending of ‘Yanoussa counts her possessions’,

Forty-nine and the obsession over

she said that, with men, it goes on a bit longer.

“I am fifty-two,” I said.

“…and the obsession’s still going!” she quipped. We both roared with laughter.

I was most interested in the Čzech writers. Their first event involved four younger Čzech writers reading from their work, translated by Jim Naughton of St Edmund Hall, Oxford University. Only one, Petr Borkovec, was a poet. I had become frustrated in the programme booklet by the, admittedly skilful, English translation by Justin Quinn, who had managed to reproduce elements of the form, such as the rhyme scheme. Nevertheless I felt the poem itself hovered somewhere behind the English translation. In the Globe once more, I introduced myself to Petr and Jim and, at the table there and then, spontaneously, began to work out with them a literal version. The poetry of Borkovec had, for me, reminiscences of the still-life quality of Osip Mandelstam’s earliest volume, Kamen (Stone).

Eventually, back in England, I continued with our efforts at retranslation, with the following result:

The lyre is weightless. Overnight,

October has collapsed onto the platform.

The electrified train grates – the station is gone.

Fifteen minutes conveys the travelling scene

to a halt whose beauty chills.

Green clouds, a poplar in blue shade,

a field at the edge of town – Arles for an instant.

And when the low tea-coloured sun collides

with the margin of the town in windows,

I catch sight of a Bethlehem crib.

The lyre is light, so I search for it

as for a wallet or lost ticket.

The younger Čzech prose writers who read from their work seemed to have in common a vein of fantasy, even surrealism. While this was occasionally breathtakingly funny, it seemed to display itself tantalisingly in front of an audience with which it did not connect. Those I spoke to afterwards, Čzech and English, were not impressed. Perhaps surrealism remains the most difficult current to integrate in the modern literary stream, the unconscious being very resistant to our attentions.

The subsequent event was a single author, Josef Švorecky. Breathless with an incipient cough-cold, he read, first in Čzech then in English, a piece concerned, like so much of his work, with jazz, but in this one he improvised a blues to a woman. All poetry worthy of the name, he said, originates in this feeling between a man and a woman. (Subsequently every effort of mine to locate the source of this reading has failed.)

In spite of such passional grounding for his work, Švorecky was decidedly modest, even self-effacing. What was striking to the visitor was the open affection in which he is held by his young Čzech audience. One questioner wondered why he was such a good person. Why indeed? Švorecky did not know but was clearly pleased.

There can be no doubt that there is abroad here a Spirit of 68. While it does my heart good to hear Bob Dylan and Janis Joplin playing at the Globe, what can it all mean to the younger generation? Do they really want to tear up paving stones and throw them at the police? Perhaps all of this is the achievement of a delicate posture. In the Old Town there is a Marquis de Sade café, into which I peeped one afternoon, finding the roomy wooden interior, with benches, tables and mirrors to relieve the gloom, very inviting. But if one was to read out, suitably translated, a few paragraphs of the Marquis to the customers, the place would quickly empty.

It is the innocence of childhood, the post-communist lull of potential. Some of the Festival presenters, with flower-wielding fixed smiles, seem to think this is all a celebration of awareness, with words and gestures to suit, a happening, a flowering of new consciousness. One strikingly tall philosophy student at Karlovy University I spoke to about poetry had read only Lawrence Ferlinghetti.

Many Čzechs wish to attach their country like a cattle tick to the belly of America. Growing up in Britain one is shielded, to an extent, from the world-wide adoration of America. Indeed I spend much of my time defending the poor things.

I had experienced a tingle of shock, close to Václavské Námestí by one of the little kiosks advertising organised tours: Terezín. The name held sweet horror. A tourist destination? But gradually it came to seem to me a duty to go, a quiet pilgrim journey amid the Festival flowerings. When would I again be in central Europe within range of a concentration camp? So early one morning a guide came to the hotel to collect me and walked me to the minibus. This tall young Karlovy student was changing his course to one in statistics. He had done some very boring work, he told me, for Reuters, as a result of which he had discovered “I am not a machine” and become altogether averse to computers.

A British couple, who quickly brought to mind the Borrowers, got into the minibus to wait but, claustrophobic, got out again. The wife endlessly berated everyone in complaint but, when her husband joined in loyally, she said:

“Now, keep calm. You must keep calm!”

Later, at the Terezín crematorium he placed a little Yarmulke on his head, so much of this behaviour would have been anxiety.

Our guide, a woman with arthritic hands in her late fifties and an ex-journalist, gave a rich and insightful commentary. However she was also pessimistic and embittered, for instance at the failures of the post-Communist governments:

“We do not have real democracy in this country.”

I appreciate the intensity of these concerns; but like my Russian friends, people here do not seem to appreciate that democracy means boredom. The Russians certainly think it means the continuation of apocalypse by other means. In Britain we have been asking whether university students should receive grants or pay tuition fees. Ah, that such a throbbing domestic issue should attend the rebirth of the Scottish parliament!

Parliamentary democracy is an admirably labour-intensive source of occupation for those with second rate talents. Let them harmlessly manage and administer our affairs, while those capable of thinking, creating and discovering get on with their work undisturbed. Surely this state of affairs is to be preferred to that in Plato’s Republic, where philosophers are compelled to set aside philosophy, against their will, and rule.

Terezín was a moving, but not a shocking or new, experience. My education seems to have included a great deal of the Holocaust. One could see that families were kept together (as they were not in black slavery), and that prisoners were fed. Matters compared favourably with, say, conditions in the Gulags. Indeed a typical Terezín barracks was strongly reminiscent of actual conditions today in the Saint Petersburg prison we visited in 1991.

Terezín was essentially a transit camp and Gestapo prison under the Nazis and the cultured Jews of the Ghetto poured forth music, writing and art, notably the sketches of Fleischmann, preserved on display in the Museum of the Terezín Ghetto, whose every caption begins, “People …” Stark, haunted and guilt-dirty as it is today, with its millions of sordid bricks, its quietness effectively conceals, what Fleischmann’s sketches reveal, that the place was a pullulating mass of human beings, some 60,000 at any time. This is truly difficult to imagine.

Given their limited resources, the authorities, Communist and post-Communist, have done well to keep the place alive as a meaningful memorial. But little Israeli flags stuck in water-pipes, occasional wreaths and witnessing candles, can never cover over, can never make more than a patchwork of fabric fragments of, the grief, indignation, preservation of children’s names. This is the best we humans can do to tame and domesticate, as a member of the historical order, this outbreak of rationalistic horror. (Our guide revolved the dilemma of “good Germans, bad Germans”.) We draw the fragments together, piecemeal, but they can never form a whole, finished garment. The facts of rational blackness keep erupting; the grief goes on; the memorial is provisional.

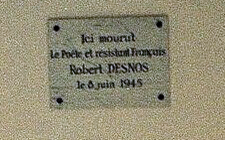

There is, at Terezín, a memorial to the French poet and resistance hero, Robert Desnos. A last poem of his was sent to his wife Youki by a Polish student who found the poet dying of typhus among survivors in 1945:

Last Poem

I have so fiercely dreamed of you

And walked so far and spoken of you so,

Loved a shade of you so hard

That now I’ve no more left of you.

I’m left to be a shade among the shades

A hundred times more shade than shade

To be shade cast time and time again into your sun-transfigured life.

Back at the Festival, I now had to bid a fond farewell to Katerina Anghelaki-Rooke. She was soon flying home to Greece and Aegean sunlight. We had both been amused at the antics of photographers and I read her in draft the little joke poem I had composed on this subject:

Photographers

They clamber over each other at the foot

of the stage, their jaws snapping,

the FAMU girls, beautiful and determined, their hair

between copper and burgundy, firing the season’s black,

the men lean, muscular, with heads forcefully crewcut.

The oversize lenses lurk like bins

to be fed with light.

And all this for writers?

But such expected adorations are ignored.

The mind of a writer is like a defunct wasps’ nest:

thousands of empty chambers rustle

in the small breeze of a thought,

a faint susurrus of indifference

to the crocodiles far below.

The concierge at my hotel, a young man, perhaps like so many a student himself, made a request. His girlfriend, a student of English, would like me to give her, autographed, some of my poems. Martiná, she had the same name as me. I found three poems that had accompanied me by accident, which he duly photocopied. I signed and wrote the same message on each one for her.

“Tell her,” I said, “that normally I wouldn’t write the same thing three times over, but I have spent the morning in a concentration camp.” He twinkled.

I, in whom these tides sometimes so majestically and impetuously rise, yesterday failed three tests of practical love.

- When there was no group collection for our guide, I failed to add my two-penn’orth to the other individual contributions.

- When a lady in the crematorium (only dead bodies were burned here, many Israeli flags notwithstanding) offered a memorial candle for sale, I failed to buy and light one.

- When a copper-haired girl, who had gladdened my boyish heart by accepting my invitation to dinner, told me she now couldn’t make it because her “boyfriend is very angry”, I failed to sympathise with the problem this had created for her.

Nevertheless, wandering in the Old Town today, I was given three chances in quick succession to redeem myself, all of which I took, in the form of Romanian, or perhaps Kosovan, refugee beggars. In the matter of begging, though loath to be parted from my money, I hold to the view of Samuel Johnson:

Why should the poor be denied such sweeteners of their existence? Life is a pill which none of us can bear to swallow without gilding. I give money to beggars to enable them to beg on. It is sufficient that our brother is in want: by what way he brought his want upon him let us not too curiously enquire.

He didn’t care, in other words, whether the recipient was worthy or unworthy, or whether he or she spent the money on drink. In this, I believe, he was adhering to the teachings of Jesus, who always urged generosity in alms – unqualified giving.

There is something in the craft and habit of begging that approaches a theatre of abjection. The posture, yesterday, even of a mother holding a one year old child, was one of profound stooping, so that, bent double, her face almost touched the ground and one wondered if she had fallen asleep.

Of course, there arises in the minds of passers-by an intolerance of this abjection, expressed in comments that can readily and repeatedly be overheard by anyone who cares to spend ten minutes standing close to a beggar. They’ll spend it on drink … She’ll go home in a taxi … He probably owns three houses. There is something about the presentation of an opportunity for charity that arouses antipathy.

Nevertheless the beggars accentuate and exaggerate all the more their postures of abjection, so that the whole performance, including the inflamed responses of passers-by, comes to seem a special form of theatre.

At the Festival, Ian McEwan had arrived in excellent form but, delighted with his audience, got increasingly into his stride and imperturbably delivered himself, in interview, of immaculate impromptu paragraphs that needed no revision at all. He was particularly funny about the interview mode itself, a genre that began with the Paris Review, and now makes it imperative that a writer explain him- or herself constantly to journalists.

He described the American circuit of literary readings, how polite and friendly everyone was, and how, alone in the elevator, he would pull wild, evil faces but, stepping out at the bottom, put on again the wide-smile, pleased-to-meet-you mask.

People are not, he said, in search of any specific information. They just want to stroke the writers gently with the palms of their hands. Like a children’s farm, put in Jim Naughton, bilingual mediator of this discussion. Yes, said McEwan, but as with children’s farms, there are fears about E. Coli. It may not always be a safe thing to do, to stroke a writer.

McEwan was particularly good on empathy. Cruelty occurs, he observed, when there is no bond of empathy between oppressor and victim. One does not put oneself in the place of the other. In this sense, the novel is an inherently moral form, as it sets out to imagine the feelings and experiences of other people.

One day, in the Globe where so many things can happen so easily, a young woman squeezed past my table to enquire whether the seats behind were occupied. No-one had sat in either of them for half an hour, I said. She duly sat herself down. Immediately a couple reappeared and, on the basis of a discarded newspaper and an empty coffee-cup, claimed the seats as their own. Gesturing to an empty seat at my table, at which I had been peacefully writing, I encouraged the woman to squeeze under the stairs and sit down there.

One day, in the Globe where so many things can happen so easily, a young woman squeezed past my table to enquire whether the seats behind were occupied. No-one had sat in either of them for half an hour, I said. She duly sat herself down. Immediately a couple reappeared and, on the basis of a discarded newspaper and an empty coffee-cup, claimed the seats as their own. Gesturing to an empty seat at my table, at which I had been peacefully writing, I encouraged the woman to squeeze under the stairs and sit down there.

“They had not sat there for half an hour, “ I repeated.

“Oh I believe you,” said the woman. She ordered a beer. I resumed my rapt concentration.

After a while a conversation easily started up. It easily took little turns, winding here and there. I could not remember making an acquaintance before in such uncomplicated fashion. We spoke English, we understood each other, we saw life through the same eyes. After a while, in the same straightforward way, she told me that last year, only a few metres from her house, she had been attacked late at night and raped, suffering extensive brain injuries. Ever since, she had experienced constant fatigue and “brain fog”. For ten minutes I sat speechless, trying not to let the tears roll down my cheeks. Such a brilliant, frail creature.

Wandering around the streets of the Old Town, I eventually succeeded in buying some small presents. In a literary café in Tynska Street, I was joined at my table by a young couple. The girl was persistently giving the boy a hard time. Nothing he could say proved acceptable. This was apparent, even to one ignorant of the language, in the rhythms of the Čzech, though these were not overly quarrelsome.

Eventually I asked in English:

“Are you happy today?”

So-so, she see-sawed her thumb and little finger.

“How did he upset you?” I asked.

Dismayed, she replied, “He speaks English too!” as if the premise had been a separate dialogue. “It’s just normal argue,” she said. I left them with a smile.

In a bookshop in a nearby square, I spoke with a girl who seemed able to answer every question and to guide my discovery of Čzech authors. Had she read every book in the shop? It seemed so. There must be stupid Čzechs, but their mothers seem to stifle them in the cradle at an early stage, so that it is impossible to come across them later on. Prague is a city in which everyone reads. But she was from Central Asia, she said, had lived in Saint Petersburg and would move next year to Spain. Then how had she learned such excellent English? “I picked it up along the way.”

In a bookshop in a nearby square, I spoke with a girl who seemed able to answer every question and to guide my discovery of Čzech authors. Had she read every book in the shop? It seemed so. There must be stupid Čzechs, but their mothers seem to stifle them in the cradle at an early stage, so that it is impossible to come across them later on. Prague is a city in which everyone reads. But she was from Central Asia, she said, had lived in Saint Petersburg and would move next year to Spain. Then how had she learned such excellent English? “I picked it up along the way.”

Girl in a Prague Bookshop

Who is not looking for love? Your lungs crave

to be packed like a barrel with smoke,

even as your fingertips tap out

a path through new Czech writing.

Who says it’s a strain, being someone,

belonging somewhere?

Intelligence senses itself in others.

You refuse one of those invitations

that so easily give rise to regrets.

The best intentions are full of bacteria.

I am no businessman, but voyage

through people and pages.

I look at people’s faces as lovingly

as at their whole bodies,

searching out the soul that, sometimes,

leaps out unsearched.

You say being a woman is normal,

but I watch the days flow back.

I have pleaded with stupid people

and mourned the treachery of objects.

We bob, laced in a seaweed web.

Like any woman you dazzle me

with my own longing.

|

Twisted Spoon Press, she told me, was a one-man-band publisher of experimental and innovative writing. Wishing to support this, I brought over to her desk all six or so titles from the shelf.

“Which one should I buy?”

“Oh,” she rose to the challenge, frowning, “It would be either this one or this.” She brought forward two titles from the pack. I replaced the others.

“Now, which of these two?” I continued.

She now demurred. “You should open it and read any paragraph, to see what it is like,” she said.

“I have done that,” I said, “with this one”, indicating a grey cover. “And I was … scared.”

“Modern literature is getting so depressing,” she said.

“It always was,” I replied. We laughed. I started to indicate a preference for the other, rose-covered book.

“But this one is very interesting, I think.” The grey again.

“You want me to be brave,” I concluded, settling for her preference, Lukáš Tomin’s Kye.

Like all young people in Prague she soon needed to go the doorway for a long gulp of smoke. My ‘Snow’ poems, a tribute to Boris Pasternak, were included in New Writing 7, I told her, perhaps the only work of mine available in Prague. I don’t know whether she looked at it after I left.

She had to serve all day in the shop, and I had an evening engagement, so we weren’t able to meet for a meal to talk further. So many things I wanted to ask her, that perhaps she would not have wished to answer…

Sunday morning and the Prague Post enables me to find an Orthodox church, Ss Kyril and Methodius, apostles to the Slavs, at the corner of Na Zderaze and Resslova. I believe this is the building where some Čzech assassins of a German general in the war, betrayed, shot themselves rather than face capture. The Nazis had wanted to flood the crypt where they were hiding.

Sunday morning and the Prague Post enables me to find an Orthodox church, Ss Kyril and Methodius, apostles to the Slavs, at the corner of Na Zderaze and Resslova. I believe this is the building where some Čzech assassins of a German general in the war, betrayed, shot themselves rather than face capture. The Nazis had wanted to flood the crypt where they were hiding.

I feel readily at home. Afterwards, in the Orthodox tradition, there is virtually no social contact, but I buy two tiny icons. One of them, a Virgin and Child, I later give to my friend with “brain fog”.

And so home, to rainy, neglected England. Why do I not like the self I am in England? A cheque from Faber awaits me for £23, being the proceeds from individual viewings of my poems over the internet. This is definitely a first.

I had accepted a P & O freebie to look over their super new cruise liner, the Aurora, in Southampton. This was impressive but a deeply disagreeable impression was created by all the members of the public crawling, like me, all over it. Some had boarded and gone straight to one of the restaurants for tea and cakes. For many, to queue to inspect the luxury of the penthouse suite was the culmination of their life’s aspirations. It may be true, as de Tocqueville said, that consumer democracy keeps people in a state of permanent childhood.

O Prague remember me! Keep alive the Spirit of ’68!

22nd April 2000

May 31, 2008

I am being treated for cancer (don’t go away). The treatment for my myeloma — bone marrow cancer — has lasted for a year and consisted thus far in oral medication. Because my immunity is sometimes severely lowered, I am under strict instructions, in the event of any high-temperature, to present myself at the Accident and Emergency department of the local hospital.

Recently this actually happened and I was able to present the letter I have been carrying around for ten months. The modern medical world is adept at capturing, spider-like, its victims and, once captured, it is very hard to escape its clutches. I soon found myself an in-patient.

In the curtained cubicle where I was first examined, I could hear the agonising pains and groans of an old lady in the next door cubicle who had been brought in by a patient black carer from an old people’s home. Amidst the rising and falling howls were occasional snatches of intelligible speech. My wife, waiting with me, procured some blankets for her when she complained of feeling cold. The lowering of the high-pitched tones, and the increase in the proportion of human speech, seemed to signal increasing calm. At one point, the patient black lady asked her what she wanted and, unexpectedly, received the reply:

I want to sit up and say my prayers.

The admitting doctor, from the subcontinent, advised, “Record, record” (times and dates of headaches and temperature levels), because “Memory is bad,” but would probably follow his friends to the better opportunities in Australia.

I welcome signs of modernity, order and military discipline, forceful management and obedience to training; clarity of purpose at the top — the doctors; but at ward level things get a little ragged, plans don’t work out, the story changes among the brown faces and imperfect English.

Although the system is brilliant the individual’s case has to be lobbied, nailed down, pro-activated. And of course everyone is worse off than me, so no complaints — nothing but admiration for the ardent nurses, the night nurses who suffer in a wholly professional manner strident lunatics, wailing retardates, drug-stirred makers of noise and mischief.

Mostly people do not do the things they say they will do. Why? Are they too swept-up by the rush of the immediate? Overworked? Fickle? As always, it is a question of making things happen, seeing things through, not in fits and starts and in response to nuisance.

I inhabit a side-room — a luxury allowed not for social but for immunity reasons. As clean and modern as a hotel room, with an ensuite bathroom, it is nevertheless bare except for varieties of technological equipment. These “rooms” are apparently modular — and lowered into place by a crane. Their floors echo. Next door is an old, and probably demented lady, sent to try the patience of the staff, especially the night nurses. Though by the morning her bedding is sopping wet and stiffened with urine, she will not let anybody touch her. Nevertheless this must be done and gives rise to animal howling that rises progressively in tone and harps on a repeated rhythm. Sometimes this rhythm seems to consist in words, which can be made out:

I hate you, you fuckers.

It is explained to me that any skin shade darker than that of Filipina evokes this response. The lady does not object nearly so much to being touched by white nurses.

During the day I hear a most surprising quadrille. She has put on her shoes, at least, and patrols the entire length of our party wall. Once or twice the steps acquire a rhythm, as if she were practising for the Royal Ballet. Long before I learn anything else about her, I determine from the weight of steps that she is female.

Perhaps it is long service as a psychologist that yields such insights. I very quickly perceive that the nurses are frequently having to deal with mentally retarded adults. Sometimes I think at first but these are children:

“Lorraine — you are in the wrong place!”

“No!” (anguished howls)

All of these snippets arrive at my ears as I lie in bed contemplating the wall or a book. I see nothing.

Have mercy upon me, O Lord, for I am weak: O Lord, heal me, for my bones are vexed.

May 31, 2008

Posted by mvlturner under

Criticism | Tags:

Allen Mandelbaum,

Andrew Lang,

Auschwitz,

C H Sisson,

Carlyle-Okey-Wicksteed,

Charles Eliot Norton,

David H Higgins,

Dorothy Sayers,

Henry F. Cary,

John Ciardi,

John Sinclair,

Laurence Binyon,

Mark Musa,

Primo Levi,

psychpomp,

Robert Graves,

Seamus Heaney,

Station Island,

Translations of Dante,

Virgil guide,

Wardour Street English |

1 Comment

1.

Dante, it seems, did not know Greek; but he had Virgil at his side.

The Mantuan had conscientiously and studiously designed his own Aeneid as a sequel to the Iliad and would have been chagrined to realise that his own, but not Homer’s, epic was available to Dante in the land of their birth. But in conjecturing a fitting end for Ulysses, Dante drew on the imagery of James’s letter in the New Testament.

According to David H Higgins, whose detailed notes accompany CH Sisson’s excellent translation of the Divine Comedy, Dante knew the texts of the Iliad and Odyssey only

fragmentarily in quotation or glosses in Latin authors. Dante knew no Greek, and no MSS of the epics were known in the West early in the fourteenth century. Dante’s esteem of Homer is based solely on his reputation as reported in later classical authors. (p. 509)

As sometimes happens with translation, the spirit and nobility of a work leap across a chasm, not only of language, but of an absent text. This particular torch is important to the relay that is often observed to be central to the progressive character of European literature. Thus Homer is complemented and extended by Virgil, who – virtuous pagan – is adopted by Dante in early Renaissance Italy as a guide, psychopomp and emblem of human reason.

That Christian rationalism has seldom been so beset as in the Nazi era of Auschwitz. And no cry more piteous has been heard than in Primo Levi’s account, in chapter 11 of If This Is A Man, of his reconstruction from memory of the ending of Inferno Canto XXVI for the benefit of Jean (or Pikolo), his twenty-four year old Alsatian companion, who

although he continued his secret individual struggle against death … did not neglect his human relationships […] (p. 137)

In the context of a first lesson in Italian, commenced immediately because

the important thing is not to lose time, not to waste this hour (p. 139)

‘Primo’ (as he is known in the camp) begins with the Canto on Ulysses! Pikolo shows his mettle (he is a survivor) by continuing to listen attentively, to wait, to suggest words, even when Levi struggles to tell him

about the Middle Ages, about the so human and so necessary and yet unexpected anachronism, but still more, something gigantic that I myself have only just seen, in a flash of intuition, perhaps the reason for our fate, for our being here today … (p. 143)

The soup queue, which they must enter to bring back a 100 pound canister of cabbage and turnip soup supported on two poles for their colleagues in the Kommando, is forgotten:

It is vitally necessary and urgent that he listen, that he understand this … before it is too late; tomorrow he or I might be dead, or we might never see each other again […] (p. 142)

Here the injured and perjured spirit of Europe cries, and is heard, through the medium of fastidious care for a text, the details of which, though many elude the memory of this man, a chemist who never thought of himself as a writer before he entered Auschwitz, come to seem, in the moment of telling, enormously significant:

“I set forth” [misi me] is not je me mis [Levi is trying both to remember Dante’s old Italian and to convey it in modern French to Pikolo], it is much stronger and more audacious, it is a chain which has been broken, it is throwing oneself on the other side of a barrier, we know the impulse well. (p. 140)

And as with every textual detail recounted, the meaning’s relevance to their situation explodes with the force of revelation.

2.

This textual force arises from a tradition, a channel of living inspiration, a world of ideal exemplars – of veracity, of clarity, even of mission, the task of the writer being to bear witness, to fulfil a national or divine purpose of the highest kind (the founding of Rome, the dispensing of eternal justice, of surviving the death camp in order to convey faithfully the intrinsic detail of the experience).

In addition to the vicissitudes of memory, which seem fatally to imperil the reconstruction of the Canto in the brief window of opportunity, as Primo and the Pikolo are

swept by the fierce rhythm of the Lager (p. 138 )

there is, for us as well as for Pikolo, the problem of linguistic access. Medieval Italian seems a special study, possibly requiring a lifetime; in this case, is there any English version which may be preferred?

Laurence Binyon (1933-43) and Dorothy Sayers (1949-62) have both ventured verse translations into English, which are highly regarded, but to which I do not have access. There are others, too, by John Sinclair (1939-46), John Ciardi (1954), Allen Mandelbaum (1980-82) and Mark Musa (1971), also unknown to me.

The internet provides a verse translation by Henry F. Cary (1892) which we may examine, choosing as specimen a pleasing extended simile (lines 27-35 or thereabouts) which compares the poet’s coming upon the eighth chasm of the eighth circle to a countryman’s view, at dusk, of glow-worms below in the valley where he has been working. Cary has this:

As in that season, when the sun least veils

His face that lightens all, what time the fly

Gives way to the shrill gnat, the peasant then,

Upon some cliff reclined, beneath him sees

Fire-flies innumerous spangling o’er the vale,

Vineyard or tilth, where his day-labor lies;

With flames so numberless throughout its space

Shone the eighth chasm, apparent, when the depth

Was to my view exposed.

This is Miltonic – contrived with the mechanical model of Latin quantitative verse in mind – but, unlike Milton, relatively inert, even pedantic:

what time … [and] then

resolutely compacted to the metre, just as ‘innumerous’ must be devised to avoid the extra syllable of ‘innumerable’. This is the fabric of Wardour Street English, inkhorn words, even fustian. ‘Spangling’ carries peculiarly the wrong association – of decorative artificiality. Moreover

when the sun least veils

His face that lightens all

requires some decoding, possibly recourse to a note (which is not supplied).

Another verse translation, undertaken with a “poetic rather than pedantic” approach, shows that even faithful versifying can be readable, that is, can flow:

The view

Beneath us was an empty depth, wherethrough

Lights moved, abundant as the fireflies are

At even, when the gnats succeed the flies.

A myriad gleams the labourer sees who lies

Above them, resting, while the vale below

Already darkens to the night, – he toiled

From dawn to store the ripened grapes, or till

The roots around, and on the shadowing hill

Reclines and gazes down the vale.

This succeeds, though, at the cost of suppressing the elaborate reference to summer.

The greatness of Dante having been lost by straining through Cary’s sieve, we turn to the contemporary Sisson:

As the countryman, who is resting on a hill,

At the season when he who lights up the world

Hides his face from us for the shortest time,

When flies give way to gnats, sees in the valley

Thousands of glow-worms, perhaps in the very place

Where he has worked at harvest or at plough;

There were as many flames there glittering

In the eighth cleft, which I perceived,

As soon as I arrived where I could see the bottom.

It is clear, now, that Dante’s nested parentheses (“at the season when … he who”) are going to cause difficulty to any translator and reader, but

At the season when he who lights up the world

Hides his face from us for the shortest time,

is graced by a note:

i.e. during the summer, when the days are longer than the nights. (p. 543)

This hurdle over, we find the agreeable colloquialism of the last line, and metrical overflow of

Thousands of glow-worms, perhaps in the very place

(devices both of which make for readability over the course of many pages), more than matched by a return of classical brio in:

There were as many flames there glittering

The contemporary fashion in verse translation for rough carpentry may be accepted in the present case, but it is a delicate balance. In passing, it may be noted that Seamus Heaney, who has acknowledged the soaring figure of Dante in his own inspiration, even writing ‘Station Island’ within the “big acoustic” of the Divine Comedy, has twice included his translations of sections of the ‘Inferno’ in his own books. The later of these, a version of Canto III, lines 82-129, ends

And they are eager to go across the river

Because Divine Justice goads them with its spur

So that their fear is turned into desire.

No good spirits ever pass this way

And therefore, if Charon objects to you,

You should understand well what his words imply […] (p. 113)

– thus confirming, in spite of serious urgency, some sense that, as regards any main verse line, the departures rather outnumber the returns.

Sisson, then, bridges the considerable gap between verse probity and prose readability, a modern achievement that may make him a preferred contemporary Dante.

Less modern, but with its own vivacity, is the Carlyle-Okey-Wicksteed version, so-called because three pairs of hands translated the three parts of the Comedy. With the ‘Inferno’ we are concerned with the work of John Aitken Carlyle. The same passage is given as:

As many fireflies as the peasant who is resting on the hill – at the time when he who lightens the world hides his face from us,

when the fly yields to the gnat – sees down along the valley there perchance where he gathers grapes and tills:

with flames thus numerous the eighth chasm was all gleaming, as I perceived, so soon as I came to where the bottom showed itself. (p. 139)

Here the syntax of the argument is stretched further, necessitating the “thus numerous” to pick up the thread of the fireflies, introduced early. But we may admire the immediacy of “where the bottom shows itself” and “where he [the peasant] gathers grapes and tills”. This cheerful pithiness of diction is sustained, agreeably to the modern reader: Ulysses and his companions, swathed in fire, soon appear moving “along the gullet of the fosse”.

If the modern trend in verse translation is to eschew manicured lines and forms imposed from a tradition alien to the Divine Comedy, then this kind of springy and mineral-rich prose is likely to hold the frail attention of the interested, but fatigable, contemporary reader, in all probability a student.

There is finally, an older version long held in special regard by connoisseurs, the prose translation by Charles Eliot Norton. This was reviewed in the early 1920s in the following terms:

[…] a prose translation, and, needless to say, a faithful one. Compared with a prose masterpiece like Andrew Lang’s version of Theocritus, it seems rather dry, and wanting in such rhythmic beauty as is well within the reach of prose. Here the austerity of Dante seems to have fused with the austerity of the Norton stock to produce something more austere than either. Norton’s version holds its own, however, with other prose versions of Dante.

But Norton was writing somewhat in the shadow of Longfellow’s own verse translation of Dante and perhaps in a spirit of quiet dissidence. Let us make the same comparison:

As many as the fireflies which, in the season when he that brightens the world keeps his face least hidden from us, the rustic, who is resting on the hillside what time the fly yields to the gnat, sees down in the valley, perhaps there where he makes his vintage and ploughs ― with so many flames all the eighth pit was gleaming, as I perceived so soon as I was there where the bottom became apparent.

Here the laws of elegant prose, rather than of regular verse, are being observed. Once again the quantitative figure (“As many … with so many”) has to be picked up after an interval occasioned by those nesting parentheses, but by now we may attribute this equally to the elaborateness of Dante and the fidelity of the translator. Otherwise the version is faultless and might well satisfy even the eagle-eyed Robert Graves, pitiless exposer of unclear prose.

3.

The criterion, then, for a translation of Dante in any age – because each new failure reveals unfamiliar faces of a turning planet – is: does it enable the trembling entry of the new reader into the world of Dante? The new reader, like Pikolo, needs to understand unmistakably the meaning of this work, the concern with salvation and judgement, with cosmos and order, in an older language; with valid living and existential truth, in a newer one.

History is the motor of culture, as tradition is of literature. In an age of relativism and officially sponsored amnesia, there is always denial of this obvious truth. But against all the odds, new questioners are born who wish to possess the cultural world they find themselves in – and wish to possess themselves.

In Europe, this sequence of defining epics – masterworks – begins perhaps with the lyric sweep of Homer, is crystallised further in the noble polity of Virgil and flowers through Christianity and the judicious passions of Dante, her greatest poet. Thus we look, as if down a telescope, from Levi to Dante, to Virgil and finally to Homer. The segments cohere, they obey an invisible sequence, they subdue the gulfs of time and interpret the inner values of a civilisation.

At its weakest this tradition gathers dust like a geranium in a museum, slumbering on the sill of yawning scholarship; but it is not its weakest that concerns us. Like a resilient nervous system, whose power is revealed only in extremity, the European tradition throws off fleshly veils of aestheticism when survival itself is threatened, when the succession becomes Homer, Virgil, Dante … and Primo Levi.

Dante leads Ulysses and his crew through the Pillars of Hercules and out towards Atlantis where, after a further five months of voyaging past the forbidden limits, they reach the imposingly dark mountain isle of Purgatory. Here, in a storm, the ship with all lives is lost, as “it pleased another [i.e. God] it should [be]”. This is an invented, but fitting, death for Ulysses, one of the

corrupt advisers, guilty of misapplying their intellectual powers, [who] are similarly guilty of the abuse of eloquence.

Levi writes:

[…] the sun is already high, midday is near. I am in a hurry, a terrible hurry […] (p. 141)

He continues:

As if I also was hearing it for the first time: like the blast of a trumpet, like the voice of God. For a moment I forget who I am and where I am. (p. 141)

Has all this urgency to communicate and remember, to recover, through exact text, the fountain of European spirituality in the most unpropitious circumstances imaginable, been in vain? Perhaps, says Levi,

perhaps, despite the wan translation and the pedestrian, rushed commentary, he [Pikolo] has received the message, he has felt that it has to do with him, that it has to do with all men who toil, and with us in particular; and that it has to do with us two, who dare to reason of these things with the poles for the soup on our shoulders. (pp. 141-2)

Thus are Dante’s words, variably translated, given a meaning and urgency that might have surprised Dante or Virgil, but would not have surprised those sinners writhing eternally in their fires in the eighth circle of that other hell.

30th August 2003

May 31, 2008

Posted by mvlturner under

Travels | Tags:

aesthetic intensity,

Avvakum,

Braille,

Coco farm and winery,

cryptomeria,

Ericksonian,

Hiragana,

Hiroshi Kawamura,

Japanese dyslexia,

Japanese interpretation,

Kanebo,

Kanji,

Katakana,

Keio Plaza Hotel,

Keio Plaza International Hotel,

Lake Baikal,

Meridian Pacific Hotel,

mikkos,

mineral spa,

Mount Fuji,

Nikko fusion,

Onsen,

Sea of Okhotsk,

Shinjuku,

syllabary,

Tanaka Hotel,

Tokyo |

Leave a Comment

We sleep tonight on the thirteenth floor of the Keio Plaza International Hotel in the downtown Shinjuku district of Tokyo. F. has accompanied me to a symposium, at which I speak tomorrow, on an improbable configuration of dyslexia, “emergency preparedness” for the handicapped and social entrepreneurship. Our warm and sincere hosts, met tonight at a buffet reception, are apparently paying for the flights and accommodation for both of us and have worked hard to prepare a programme, translate my talk into Japanese and organise “study tours” for us. We expect, on Sunday, to visit a winery that produces a world-famous champagne (its most recent outing was at the G8 summit), sleep in a “Japanese room” (on a mat?) and bathe in a hot spring.

We travelled a quarter of the way round the world on an uninterrupted twelve-hour flight, never leaving Russian airspace. Because we were heading east, to the plane’s (roughly) 500 mph must be added 1000 or so mph of the earth’s speed of rotation in relation to the surrounding space. As Australia woke into sunlight, Southern Africa dipped into darkness. I had thought China was vast and Mongolia a large portion of the Far East. Not a bit of it: China was a well-defined province and Mongolia a mere region to the north of India. The vast strip of planet above them passed beneath us with scarcely a murmur of forest and mountain, marked green on the flight data map but empty, apparently, of any defining cities or aspiring population, so great is the remaining mystery, even to cartographers, of all that vast space.

Loosely clothed, well-prepared and richly entertained (books, tapes), F. and I were in addition able to expand – in this plane perhaps a third empty – across the aisle into neighbouring seats with leg-extension possibilities. Drowsing between visits of cabin staff with snacks and orange juice, we forgot the time our bodies thought it was and surged forward with the horizon-cresting sun, into the time-frame of novelty and adventure. Around 5-6 am I switched off all lights, screens and musical equipment and drowsed in relative comfort, afraid no longer of the death panics that used to visit with airplane sleeps.

Only as the plane curved southeast beyond the upper slopes of Lake Baikal, known to Avvakum and latter day ecologists alike as the largest freshwater lake in the world, did we leave the mysteriously vacant strip of endless green space and head down towards Japan, the Koreas and the Sea of Okhotsk in multi-layered blankets of darkness. My first consciousness of Japan, therefore, was of light flooding the cabin several hours later when I woke after a serious sleep, F. having raised the shutters of her two windows. After a while she said, “Look! Mount Fuji!” and I looked over her shoulder down at the ground, corrugated as an elephant’s hide in close-up. But I could not see it. Then I saw it, not on the ground but in the sky, its magnificent white peak chiming with the whiteness of snow and cloud, but raised high above the surrounding environment.

Then, just as the moon used to stay constant in the sky however much I ducked and dived through the lanes and side streets of Walthamstow and Barkingside, so Mount Fuji kept reappearing as a noble constant whatever descending turns and circuits our plane executed in its approach to Narita. In its sacred presence the light kept on flooding my mind with its first impressions of Japan. Though – at 5-6ºC – little warmer than the Heathrow we had left, Tokyo and Narita seemed to sing in a daze of luminance, even after we stepped outside to await, with the help of boys with lists, little English but Japanese intensity, the arrival of the airport limousine bus that would ferry us, along impressively static and toxic aerial decks and slip roads, through the Tokyo rush hour directly to our hotel.

The conference itself took place in a long third floor lounge in a business building. The rostrum was equipped with laptop and PowerPoint and wired up so that a microphone transmitted the speaker’s words to two ladies in a translation booth at the back of the hall. Once it existed in Japanese, a team of four stenographers with laptops, writing in series, produced real-time captions which floated up a large screen at the front. In addition, members of the audience had individual relayers with earpieces, so that the talk could be received in the appropriate language. A smiling young man rotated around the room, imperturbably ensuring that all the technology worked.

Nevertheless all this electronic facilitation served, as in Russia, an authoritarian monologist world of expertise. Members of the audience slept and even those who remained awake were quite passive: there was very little audience participation, even when questions were invited. Indeed much of the matter being delivered was vague – always a sign of public or otherwise charitable funding – with buzzwords floating around like

community … marginalised … project … task-writing … initiative … disadvantage … co-operative … win-win … potential … new mood.

The shadowy infrastructure of fragile funding was illuminated by strokes of resolute optimism.

The wall-to-wall technology thus served to render a field of loose but cheery fluff for a small audience, among them journalists, entrepreneurs, bureaucrats, academics, who if they stayed awake, were anxious to cement contacts who could be useful to them on their next visit to the U.K. This was the world of the Japanese NPO – not for profit organisation – and the skies of the voluntary sector were occasionally illuminated by the fervent, furtive fires of lurking passion, something which if not to be altogether concealed was also not to be bruited about either. But the anaesthetic of formality was heavy: I was far less spontaneous as a speaker than I would normally be and, pacing myself to the translators in the box, covered too little of my talk in the allotted forty minutes and had to foreshorten it, even though the ladies had said they found it much easier to interpret spontaneous speeds (“people speak as they think”) than the reading even of a prepared text they had seen in advance.

There were what appeared to be several felicitous mistranslations:

Art can be the vehicle for the invasion of the community.

And early on we had been enjoined to do all we could for disabled persons, who would thus be permitted to realise the “divinity” that they had within them. And was that really a reference to an “Institute for a Healthy Future”?

Once again:

|

HIRAGANA

|

syllabary for Japanese words

|

|

KATAKANA

|

syllabary for non-Japanese words

|

|

KANJI

|

Chinese characters appointed 1000 years ago and

morphologically combined.

|

11th February 2003

The girl seems divine until she opens her mouth to ask for a cheese sandwich; the notice in stark, splashing Kanji – black on white – in the sanctuary seems a revelation until it is translated: No Smoking.

Somehow it is a mistake not to remain in our divinity. With our divinity the prepositions get tricky with numinosity.

I asked Phillida Purvis, who has been coming and going to Japan for years, whether she had ever come across a rude shop assistant in Japan. “Never,” she replied without a moment’s hesitation, and went on to tell me how shocked she had been by comparison behaviour in London.

One evening we wandered around the streets close to our Keio Plaza Hotel in the Shinjuku district of Tokyo. Every Japanese was helpful, though English was not widespread. As the rain began to freckle, we passed a stall selling the latest models of mobile phone which, at the moment, in Japan, take photographs and transmit colour pictures, though text is unknown and international calls are impossible. It was possible to peel each one off its stand, to which it was attached by a Velcro strip, and experiment: it was fully operational. Moreover the stall was unattended: whoever was in charge was not hovering. This situation was the one, of all those we experienced in Japan, least thinkable in the UK, where mobile phone theft is an epidemic.

There is a novel – and to Japanese disturbing – phenomenon of unemployment and homelessness in Tokyo. But one homeless chap we passed on the street at least, amid his blankets and cardboard, had his mobile phone.

We lodged on the 30th floor of the 45-floor Keio Plaza Hotel. But the lifts were so fluent we reached the 30th floor without me noticing – I was studying a leaflet. Everybody else waited politely for me to get out, but when I didn’t, resigned themselves to the upward progression.

I discovered a coffee shop in the basement of the hotel where, on a tablecloth with orchids, an exquisite waitress whose life story I longed to listen to was prepared to lay cappuccino after cappuccino. I sat and wrote there one evening, whey-faced and wasted though mirrors reveal me to be: in Japan I prefer stimulation. There is much to be said for a mean national IQ of 106. Order is civilisation. So is aesthetic intensity. Mrs Yamauchi, who seemed astonished at my contention that individualisation results from Christianity, described her mother wiping humidity from glass panels: three horizontal strokes, three vertical strokes. At the next table in the restaurant, however, a vast American Negro, full of high-spirited jive talk came to sit with his Arab friend. The Negro seemed to want to fill the restaurant with his noise and to generate a spirit of uninhibited stag-night risk-taking! However the more contained Arab commenced a long, involved conversation with someone on a mobile phone complete with an aerial that trembled close to his temple. It seemed that he was not at all eager to talk to his Negro friend. Gradually the man deflated, though he did not easily relinquish a style of communicating that seemed, here, absurdly out of place and empty.

On the landing of the 30th floor a wheelchair approached conveying an elderly Japanese man whose skin had a leaf-like transparency. He was pushed by a younger man who disappeared and reappeared, and accompanied by an elderly woman in simple apparel with a small dark pattern. The lady performed a little ritual bowing and clapping as a charm against the uncertainty of the journey, before getting into the lift. The old man stared at me and through me, serenely unwilling to smile, but also without trace of a frown.

We had two free days remaining in Japan after the conference and found good reason to be grateful that we had surrendered ourselves to our hosts’ ministrations. They orchestrated for us every kind of agreeable experience. After the symposium we repaired to a Chinese restaurant where a succession of little dishes was served, conversation flowed and time receded. The soup was controversial: was it shark’s fin? No, it consisted only of the swim-bladders of certain fish. I was flanked by two ladies excited about dyslexia. The one to my right, to whom I had to emphasise that there are no short cuts, preferred like most teachers not to listen but to talk. She advanced her theory – about Japanese brains and reduced self-esteem – translated by the more able lady on my left. After one hefty gobbet I felt more was expected of me, so I said (to my interpreter),

“I understand what she is saying but not the point she is trying to make.”

“Me neither,” came the instant reply.

After dinner everybody who was anybody in Japanese dyslexia and social enterprise lined up for “picture time.” My camera, handed (by F.?) to a Chinese waiter, refused to work – for him, for her and for me. Gradually I surmised that the time had come to replace its two lithium batteries; but the photographic moment had passed. Other cameras, mostly digital, flashed, including F.’s, so I hope the grouping will end up in a Japanese sequence in the album.

On Monday a long coach journey began with a tortuous exit from Tokyo complicated alike by a bog of traffic and a prolonged extenuation of suburbs. Gradually we came to rice-growing areas and older, tightly packed houses (there are few old buildings in Tokyo) with steps, balconies, mezzanines, bonsais, cars squeezed into doorways and an occasional inhabitant at peace under his vine.

Our first port of call was the Coco farm and winery, founded in the 1970s to create healthy, uncomplicated employment for the 100 or so adult inhabitants of a nearby “school” for the mentally handicapped. This curious mixture of business and the not–for-profit organisation was explained to us by Bruce, an engaging Californian wine expert, who had come to trouble-shoot the humidity and mould (Japan’s is a highly unsuitable climate for grape growing) in the mid-1980s and stayed on. After years of cultivating the few skills of wine drinking, I started to understand something of how wines are made. The founder, now 82, put in an appearance at lunch, poised, humorous, elegant, holding a wineglass in his hand by the stem as he spoke. The story was repeated with much amusement how, when he had told some visitors he had first acquired a taste for alcohol at the age of four, one lady had said,

“That’s too late!”

I asked him how to turn an idea into reality. He replied,

“First I bought a mountain”.

Our table at lunch was liberally supplied with wine – two whites and a red: this winery simply doesn’t make wine with sub-standard grapes, but discards them, so its high quality is famed throughout Japan – and evidently this was true of the other table also. So when we tiptoed back up the hill afterwards we were more than a little merry. Unfortunately the director and deputy of a local group-home (or hostel for adult mentally handicapped), to which we were going on, were seized at the sight of us, by a fit of provincial self-importance. We all sat around a table on the café terrace as coffee was served and set ourselves to the business of exchanging name-cards and making introductions. Then the director, with an air of a Soviet official, stood up and began making a speech to his tiny inebriated audience. As we collapsed with hysterics (which had no effect on the impervious man), a struggle ensued to cover up our mirth with a semblance at least of straight faces to redeem this most un-Japanese lapse from respectful politeness. The pair made repeated excuses of having busy, important meetings to get to, but seemed never actually to depart, which would have brought their humiliation to an end. It was some time after we had climbed back aboard our bus that our hysteria began to abate. The Russians, I thought, would precipitate such a situation – of speeches and pompous formality – but would not then laugh at themselves or permit themselves to be laughed at.

We moved on to two group homes which were an affectionate delight, but something of the same kind of situation persisted. Most societies arrange this kind of provision in a fairly similar way, so perhaps it was not really necessary to unravel the strands of central and local government money and private employment that held together the fabric of a passable life for all concerned. Nevertheless John Smalley wanted to know why the residents earned “so little” and what degree of “financial autonomy” they could have. At this persistent line of questioning our provincial director’s speeches got longer and longer, as he felt exposed to possible criticism . Meanwhile, as often happens after drinking, our little party was, one by one, falling asleep. Eventually, summoning up diplomatic skills acquired in innumerable Russian orphanages, I stepped into the breach and made a speech of my own. It was easy for even the casual visitor to see, I said, how successful had been the efforts of the Director and his wonderful staff. Comfort, security and equanimity were evident in the smallest details of the life around us. (A nursing assistant had quietly ascertained the number of teas and coffees and handed round a tray, while, at the table, a middle-aged downcast woman, absorbed in drawing in a pad on which her pen had produced not very much, had been squeezed round the shoulders by the kindly house-mother standing behind her and had visibly brightened.) Now the Director’s speeches became shorter and shorter, but still nobody moved. Hiroshi, whose head had stopped jerking, had descended tranquilly into deep sleep. Then F. entered the fray, posed a few more questions about the obscure organisation of the place and, with an almost Ericksonian air of finality, leaned back and said, “Thank you!” At which point, everybody stood up.

On we went, in our coach, to the mineral spa at Onsen. Here the Roman script was non-existent and everything was done according to Japanese custom. Stooped from a lifetime of toil, country couples would arrive – he with short sight, she with little steps – wrap themselves in kimonos and top-jackets and enjoy the waters’ healing properties. Apart from the latter, one has to imagine a combination of jacuzzi and Turkish steam, for neither of which, perhaps, would one have to make a very arduous journey in Britain. But this was all a cause of deep excitement in our party, for foreigner and Japanese alike. Moreover we all met up for a traditional Japanese supper served at a long low table in a room apart, at which we kneeled, cross-legged, on mats or, in my case, leaned with one leg stretched out and my back supported by an upright seating supplement. The absence of chair and table, combined with irritable fatigue, would mean that I could not write and I woke next morning with a severe back pain. However, it was my birthday and, goaded by Hiroshi who sat opposite, I opened the meal with a toast. Many little dishes appeared with unidentified small portions of beans, vegetable, seafood, aparilla herb, tofu (a curd of soya beans), orchid flowers that turned out to be tiny squid and, ultimately, bowls of rice (as when the fat lady sings, you know the meal is ending when the rice arrives). Best of all, this meal was the long-awaited opportunity to get to know the short, wizened, sad-eyed but ever-twinkling Hiroshi Kawamura, the Renaissance genius behind the whole adventure. He had been a librarian at the University of Tokyo for seventeen years, until he was given the task of programming a Braille system for a brilliant, blind student. The system of “talking books” and “tables of contents” that he devised – Daisy to its friends – has proved to be useful to many others also, including dyslexics. He now chairs an international forum on standardising access protocols for the disabled of many countries. Being in the presence of a truly gifted individual was, as always, an experience both exhilarating and calming.

Iranian women have traditionally had their scope confined to core female functions and F., though herself more than emancipated, has always reacted to this intensification of the female by being intensely feminine. She talks about women, not just as one of them, but as an expert, and tends quickly to fascinate the women she meets. Japanese women proved no exception. “I’m an old maid,” confided Yuko, beaming, within minutes of meeting her. At the Chinese restaurant, the junior high school teacher to my right, only towards the end of the meal summoning up the spirit to address F. publicly across the table, chose to congratulate her on her appearance, meaning her fine clothes, but still more her exquisite, youthful looks. Following their shy, giggling retirement to the bath house together, F. reports that Japanese women have small breasts but large nipples, narrow waists but broad bottoms, and are all in perfect trim with no flab or problems of overweight. They all took in their little pots and sat on them in a row, obediently filling bowls with water so as to conserve the fresh supplies, and washed themselves diligently. After the pool, where the water bubbles up through little holes, F. gave them a lesson in the many arts of make-up. The Japanese ladies were amazed to learn that their own brand, Kanebo, was F.’s favourite.

After a deliciously cool night on the floor between tatami mats and duvet, we rose, packed once more and headed in our faithful bus to Nikko, a town not far to the north of Tokyo with a famed national park and temple complex that is a world heritage site.

Even the approach to Nikko involved a physical ascent, as the immense presence of a group of snowy mountains mysteriously revealed and concealed themselves ahead of us behind trees, streets thick with overhead wires and signs and self-importantly posed, jutting buildings. Once more the day and the environment were full of light, girdling the coach and its little party dazed with happiness, the villages and bonsai-dotted homesteads and stimulating the cameras to emerge from their dark bags and glance hurriedly through the generous bay window at the front of the bus at the scenes that unfolded in quick succession. We were passing through an area famed for its Japanese cedars – sogi or cryptomeria – as our driver, a part-time rice farmer, was pleased to remind us.

We emerged from our bus onto a muddy level and unfolded the wheelchair of Rayini, the Taiwanese girl student of five languages who is of the party. Thereafter she progressed either on foot or pushed by one or other of us, to the very topmost temple, jibbing only at the 270 steps that crowned the ascent to a final shrine. Snow lay on the ground to the sides of the paths and the great central avenue that led, by steps and levels, from temple to temple. The air had a pleasant chill; later F. was to pooh-pooh the guidebook pictures of dragon-ornamented lintels framed by spring sunshine and April cherry-blossoms, claiming that the snow and the early darkness (falling from four o’clock) had added specially to the atmosphere.

We toiled unhurriedly up the pathway. The pilgrims seemed to consist disproportionately in young people, especially loving couples seeking some sort of blessing on their intentions. On me the unhurriedness had the effect of loosening my body, so that I took long, slow strides, enjoying the shifting balance of my weight going up steps or coming down. Occasionally we stopped to absorb information from our guide, who waved her green flag like a railwayman, indefatigably interpreted by Misako, of whose planning efforts today was the fruit. Or more often we composed our thoughts in photographs, thus absorbing visually the centuries concertinaed detail.

Why such happiness? We all felt this, a sense of charm, or good fortune, or grace descending on us as we rose up the mountain, the sense of climax increasing with the altitude. The inner mists cleared, the malice fled, the harmony (kio-chio) prevailed. As a little party we enjoyed a feeling of unity in which artificiality played no part. Delighted to find that my own Christian faith enabled me to rejoice in being, I paused in front of a little shrine and thought: God is not just great – he is infinitely great.

Many forms of aesthetic intensity are characteristic of the Japanese, and these can degenerate into mere compulsion. But the flair for detail, and for conveying presence of mind into ritual and creative gestures, intensified at the summit of this very Japanese mountain. Priests, guides and mikkos – vestal virgins in robes as red as cardinal birds – seemed enormously busy and active, channelling and enlightening us tourists. We were led – without shoes and with cameras switched off – round rectangular temple corridors and balconies. Words cannot possibly convey the cumulative atmosphere created by the Chinese carvings (dragons, children), the worked metal and wood, the great bells whose noonday ringing so inspired F.. Layer upon layer of slatted or tiled roofs rose above each other, and above us, and above all stood the cedars, gaunt, curtained, gloved in snow, bound by the priestly Japanese in hoops of iron, but themselves more priestly, lofty and ancient (one was 800 years old) than everything else around them, nobler than the samurais, fiercer than the bushi, more enlightened than the forefathers of Zen and Shinto whose wanderings ended in this place. Their presences were like spirits, someone said: “They are a kind of god”. Yes. I thought, once again pressing onward up some more steps, and the female sexual organ is a kind of god also, but one cannot say so.

Now at 38,000 feet we are following a more northerly path than on our outward journey, heading away from the uncharted (but not uninhabited) expanses of northern Russia towards the Barents Sea, having negotiated, first the Lapter Sea, then the Kara Sea, known to cartographers but not to me. Indeed if we do not take a southerly turn soon we may find ourselves at the North Pole. I feel I may now have covered the greater part of what I wanted to record about Japan. I have been writing for six hours, and the excitement scarcely dies down. Incredulous, I see other people sleeping. But perhaps I’m not finished yet.

Now we’re turning south at last, over an unnameable icy spur that divides the Barents and the Kara seas. I’m sure that the Arctic fish shoals and submariners far below are oblivious of our shadow, as we pass in the opening eye of sunrise.

Will I carry anything of this serenity and energy away from the Nikko mountain as I leave? Perhaps. We descended to our bus eventually as the light began to go and returned to the forecourt of the souvenir shop where we had initially picked up our guide and where the coach had in the meantime parked free of charge. In return we were expected to go inside the shop, where a tray of green teas awaited us, use the toilets and cast an eye over the unutterable kitsch on the shelves. This we duly did, discovering (and buying) some treasures – mainly cups – lurking amid the candyfloss and day-glo colours of the children’s temptations. Back on the coach Misako said we had done well to co-operate. I had heard this word used, in a faintly inappropriate way, at the end of the symposium also: “Thank you for your co-operation”. It struck me that this was a hugely important concept, kio-ryoku, co-operation, or kio-chio, harmony.

In the valley between the two mountains rushed a torrent and we crept back up the river to approach our lunchtime destination which sat on an eminence above us, the Kanaya Hotel. This is a world-famous classic hotel that has only recently put aside – but still displays – its blue porcelain. Here Einstein, George VI and others have stayed, their bills of account proudly displayed, complete with signatures. Opting for “western” food for a change, we sat to an alcove table exquisitely laid and consummately served to the highest possible standard. Conversation turned briefly to social harmony (Japan) and rugged individualism (Britain), to Iraq and America and the meaning of culture. But there was a new awkwardness, perhaps because of the Western setting. Nevertheless, at our end little Rayini came to life when she lectured us on the five basic tonal “positions” in Taiwanese and Mandarin Chinese – her own language (my lime-green Virgin Atlantic notepad was out again, to capture the vital words and signs). How much a person’s own language means to them; how its use activates them. As always I had coffee and requested a cup of hot water for F.. We discussed “kinds” of tea, a slightly baffling question for the Japanese, who are fascinated, too, when I drop Hermesetas Gold pellets into my hot drinks. When the hot water arrived, I produced an Earl Grey teabag from my trouser pocket and held it up. “Do you know what this is?” I asked. When they didn’t, I said, “This is called marriage!” After an initially literal reaction they got the point and laughed merrily.

And so the story ends, with a coach trip back to reality – or at least normality – as embodied in the Tokyo rush hour. Our very tender goodbyes had to be said on the porch of the luxurious Meridian Pacific Hotel, where we were to experience the epitome of refined comfort (breakfast overlooking waterfall and pool) for £50 a night each, the price comparable to that of the Travel Lodge up the road in Bagshot. Will we meet these very sympathetic friends again – Misako, Yuko, Mrs Yamauchi, Rayini? Our gratitude to them will not quickly die down. Then our English friends, John and his son Rick, who travel to the same destination at the same time by a different airline, must be bid a fond farewell at Narita airport. We have all shared in an experience unexpectedly sublime. And we must say sayonara to Japan itself, whose aesthetic intensity and ingenious hard work (kim-ben) are embodied for the last time in shop after shop of exquisitely produced goods in the terminal’s unhurried, uncrowded arcade. Considering this was not even a holiday, Japan has turned out to be another in a lifetime’s mysterious chain of snow-covered peaks.

Nikko fusion

This mountain has approached all day

and now bows a welcome through archways.

Somewhere a clock strikes noon or afternoon,

far or near, chimes in the lustrous dark.

Generations of round-eyed men have laboured

to bring each peak and pebble to visibility.

But how little trace there is of insight, how it evades capture –

the notebooks, the cameras.

Far below the surface something is shaken.

A mountain becomes a wave.