Please send any enquiries by email.

February 2, 2016

Please send any enquiries by email.

March 7, 2010

As a young man I rejoiced in the poems, which circulated among us, of Christopher Logue. We had his poster poem on our walls; we carried about his ‘Red Bird’ jazz-and-poetry disc (these were both firsts). As a schoolboy, I had invited him to the Royal Grammar School, High Wycombe, but he would not come because we could not pay him. My poet-banker friend Jack Osbourn, who like Logue had read his own poems on 11th June 1965 at the Albert Hall, on the occasion of the International Poetry Incarnation, admired the chutzpah of Logue’s arrogance. My lovely CG went off and slept with him (Logue), as a sort of trophy. I met him once or twice amid the shouting din of Faber’s summer parties in the early 90s, when little in the way of communication was possible. What I did not know was that, amid the gathering success of Logue’s Homeric ‘versions’, Christopher Reid was editing a new Selected Poems of Logue.[1] These I have just now finished.

There are one or two stand-alone poems which I would salvage for my Universal Anthology of Modern Poetry in English:

ּ

and, after Villon, ‘Caption for a Photograph of Four Organised Criminals’:

And it has been a real pleasure to be reunited with some old friends ─ which I found I knew by heart:

ּ

ּ

Popular appeal is part of his popular appeal. But the real revelation of this revisiting is of the desolate salt wastes that surround the Cyclades of the Homeric versions. There is really nothing there. In spite of the technical prowess, all is fragmented, miscellaneous. Even some individual successes cannot redeem the impression that this man has nothing of his own to say. The tiger is caged by his own bleak vision. One cannot help but notice that he is no Walcott, Cavafy or Ken Smith:

Many of Logue’s shorter, earlier poems embody a spirit of dissident radicalism eager to be mantled by his readers’ youthful empathy ─ but in favour of what? It is impossible to say. Now in his 80s, Logue seems to have been picked up in the 60s by the tide of hipsterism for which he had been waiting without knowing it. His shining lyrical virtues were suddenly recognised by a large, shaggy audience that asked no questions. For some reason ─ loyalty, perhaps ─ he still wishes to be associated with Alex Trocchi.

Logue seems to be very much more talented ─ in a way Ben Johnson would recognise ─ than similar vernacular poets of our time ─ Cohen, Ginsberg ─ but to have been unable to break out of a confining definition of the lyric poet. There is no doubt that his variations upon Homeric themes excite by their huge vernacular energy:

But a comparison with more orthodox ‘translations’ shows how much is left out. Logue really just freewheels, filling in the details in inspired ways, while omitting everything in Homer that might tell us what is going on. He carves the lyric out of the narrative.

Among the non-Homeric shorter poems, through which the hardy reader must navigate knot after irresolvable knot, he several times attempts an explicit narrative ─ ‘The Girls’, ‘Urbanal’ ─ but loses himself in recondite vocabulary,[8] syntactic ingenuities,

or:

and just plain obscurity:

or:

or:

But modern poetry should be difficult, shouldn’t it?

Nevertheless, an occasional classical neatness springs up, ever fresh, in anapaests and iambs, when you are least expecting it:

Or:

To an astonishing extent in one so ‘revolutionary,’ many of the poems are literary, in the sense that they arise from starting points in old books. However, no amount of footnoting will render interesting a poem that has already left you cold.

[1] Christopher Logue, Selected Poems, ed. Christopher Reid. London: Faber and Faber, 1996. Page references are to this edition unless otherwise noted.

[2] ‘ Cats are full of death’ p. 51.

[3] p. 53.

[4] ‘O come all ye faithful’, p. 133; a poem worthy of its resonance with Creeley’s ‘Love comes quietly,’ written about the same time.

[5] Ken Smith, closing lines of ‘Departure’s Speech’, final poem of Terra. Newcastle-upon-Tyne: Bloodaxe Books, 1986, p. 89.

[6] A word of Persian origin, meaning sedge.

[7] p. 141; from Book 21 of the Iliad,

[8] See galingale, above; I have also looked up hyoid (a U-shaped bone at the root of the human tongue), mucid (mouldy, musty) and snood (hairnet).

[9] Logue’s own note to this word is: “‘Aurene’ = shining gold; scans as in ‘serene’.“

[10] The awkwardness of this must, albeit reluctantly, reduce one’s enthusiasm for the spanking modern version, ‘Gone Ladies’, p. 81, of Villon’s ‘Where are the snows of yesteryear?’ Ballade.

[11] ‘Urbanal’, p. 131.

[12] ‘The Song of Autobiography,’ p. 9.

[13] ‘The Girls’, p. 120.

[14] ‘Fragment’, p. 89. What is the city’s cut? And how, along it, can booms tend cinderbeds?

[15] This mellifluous passage, in an iambic pentameter measure which has usurped, at the last minute, the steadfast narrative pulse of anapaests, ends (p. 127) the extended but very strange narrative poem, ‘The Girls.’

[16] ‘Fragment’, p. 90, a poem whose unevenness we have already noticed and in which these pentameters, knocked out as meanly as any by Robert Lowell, sit like duck’s eggs in a basket of stones.

February 7, 2010

It is in many ways a great honour to be allowed into this book.[1] The poet, bereft of his wife of 29 years, has written a short poetic memoir that seems neither indulgent nor egotistical, in which he seems to find his effects almost accidentally.

It will be recalled that on two occasions in the Gospels Jesus utters similar sayings:

But again, perhaps more inclusively, he also puts the statement in its reverse form:

These then are the ancestral memories that gather around a word. Christopher may also wish to suggest the scattering of ashes that did not occur for Lucinda (20 October 1949 – 6 October 2005) since, at her request, her body was donated to medical research; as a result, the poet reflects, as he passes the Institute,

Published four years after her death from a brain cancer, A Scattering is a book in four sections and benefits from its own organic form:

Christopher was my poetry editor at Faber and I was privileged to meet Lucinda once or twice. My previous favourite book of his was Katerina Brac (1985, 2001) which adopted the persona of an East European woman and did so in a consistent way as a sustained act of empathy and historical imagination. From an early ‘Martian’ emphasis on description shared with his tutor and mentor Craig Raine, publisher of the new volume, both men have moved away into greater emotional depth, Craig notably into an ‘epic’ family history, History: The Home Movie (1995). Christopher’s more persistent ‘ludic’ tendencies can seem to have something in common with Max Beerbohm’s later preoccupations, but there is very little gaming in the present volume, enlarged by existential challenge.

To give some idea of the enormous, yet also somehow selfless, achievement of this collection, I want to visit certain poems by means of excerpts.

The heart of the book for me is the moment at which the reader feels most privileged, when he is admitted into the room at the moment of Lucinda’s death. The poet takes his arm off his wife’s chest and

All this is told just as it is, undecoratively, with the moment’s own grandeur brooking no augmentation. ‘Kisses’ just ‘followed’ (things just happen). But notice that ‘unhurt farewell.’

Here and there, we are treated to the couple’s own deliberate secularism, occasionally to an extent which lapses into obscurity, at least for this reader:

But of course the facts of the main experience run clean in the opposite direction for a poet whose honesty seems in some mysterious way frequently to transcend such selfhood.

Of the more conventional and ‘finished’ poems, ‘Soul’ comes high among my list of favourites. Here the poet charmingly describes the internal clankings of what appears to be a kind of pregnancy. But the poem ends:

Finally, an actress, weaver and celebratory gardener, Lucinda appears, untrammelled by her husband’s poetic deliberation, in many of her glorious incarnations:

Christopher allows himself little that is self-indulgent or even what an entomologist might regard as personal. At one minute we glimpse ‘a voyeur’ grateful for the fortification

And then, most revealing, in the last poem we hear:

These are not isolated moments, but cohere in a natural but ordered outpouring of grief, recollection and resurrection. What is real in us lives on.

[2] Matthew 12:30, NIV, 1984.

[3] Luke 9:50, NIV, 1984.

[4] Afterlife, p.49.

[5] Afterlife, p. 49.

[6] Soul, p. 39.

[7] I had to look this up: “Fabric made using an Indonesian decorative technique in which warp or weft threads, or both, are tie-dyed before weaving. Malay.” New OED, 2003.

[8] ‘A Faust moment’, p. 59.

[9] An Italian Market, p. 48.

[10] ‘ The documents are gathered’, p. 61.

February 3, 2010

In rolling royalties he took an innocent delight

but what, in baring his soul, had he really wanted?

Nothing it seemed to him gave anyone the right

to anatomise the growth that he had merely planted.

ּ

Those corners that most excited them remained dark for him,

dark and consequential, like a late summer sky

as it banks away towards evening and the stormy rim

of darkness veiling and unveiling hillsides of rye.

ּ

He thought it would be enough to tilt his page

to catch the rain-washed strokes of light,

to leave it all incomplete, a cloudy rage,

and throw a tarpaulin over it as one would a boat.

ּ

But even then knots of people stood around

wanting a word, a signature, above all information.

Did he feel flattered? So long as they didn’t surround

him he could edge away, pleading engagement, the woes of creation.

ּ

He had meant what he said: he stood on the edge

of the known world of noisy, parasitic business,

and on those reckless enough to approach his ridge

had urged safety and caution as one might a straightening of dress.

ּ

How many repetitions does it take? The broken sky

leaned dangerously but still the multitude

came on steamily, as if they detected a lie,

and so far he had managed not to be rude.

ּ

Here was the earth, the covert, the blanket of red leaves

that discreet October had kindly provided,

a stump wrapped around with the silence of foggy trees,

where nothing further could be exposed or derided.

ּ

It wasn’t exactly peace and far from solitude.

There were many theories, but no one thought he was a saint.

With neighbours moving remotely he could avoid a feud

and brood in silence on his mysterious taint.

January 30, 2010

The collapse of artistic tradition in poetry is nowhere shown as clearly as in the USA. By tradition I precisely mean knowledge, craft, expertise. One doubts that a real feeling for the English-language poetry tradition can be gained even in colleges and universities any more.

Be sure: tradition is not a matter of pastiche and form is not a matter of metre and rhyme (bit and bridle). Tradition is as TS Eliot said it was, a changing body of experience that modifies the present and is modified by it:

Form is the means whereby art achieves its transformation of reality and, in poetry, this means such considerations as length, verse or stanza structure, speakability, momentum, voice and register, drama and intensity, rhetoric and eloquence. With the systematic introduction of half-rhymes early in the last century (see Wilfred Owen’s Strange Meeting), poetry became a vast acoustic with long-held echoes. The accentual or stress-syllable patterns, characteristic of English, have made the iambic pentameter an unfailing harbour from which adventurous barks forever set sail, or to which they return, rather like the French alexandrine (hexameter) which is native to the different, syllabic prosody of the French language.

Free verse is a sort of poetry that walks by itself, very much a speaker’s voice and often appropriate and successful, but normally now a characteristic of the flood of illiterate adolescent outpouring that has become the steel-hard, inexorable convention.

Consider the following:[1]

In these 93 words of prose, one may detect some ambiguity in the first sentence: Is it ‘you’ or the weather girl who pivots, smiles and points to the other coast? Dance here is used as a transitive verb. Cannot ‘What does the world’ have the question mark it needs? Is the motel in an ‘anywhere town’ or is an example of the latter visible, ‘across the bay’, from the motel window? Cities are pilloried as Sodom and Gomorrah, emblematic of ‘lies’ and self-blinded lives’ (with no explanation). In keeping with this rejection of modern worldliness, satellites send and receive ‘emptiness’ (including to those who arrive successfully by SatNav after a complex journey). Perhaps thumbing the remote is evidence of the contemporary inanity of the poet’s companion.

The passage appears to be a mere grumble, confided perhaps to a notebook, to be taken up later and turned into a poem, or abandoned. Good clear prose obeys certain laws of basic communication and this specimen enables us to see its flaws readily enough.

But the passage has been rendered as prose by me! Let us reintroduce the line-breaks with which it was endowed at publication by its author:

Now we are certainly taking up more space and, for those readers lacking stamina, short lines enable more rapid breathing. But what exactly is added to the passage by thus inserting carriage-returns all over the place? Perhaps one ambiguity becomes clear: it may be the companion, because of the line-beak after ’girl’, who watches the weather girl, dances her (the companion’s own) hands, pivots etc. But in this case, why not resort to the humble comma? Line-breaks are the defining feature of poems; but here the final line-break seems to have been inserted after ‘shamelessly’, dividing up a verb phrase, simply, one feels, because the poet did not want a line that was too long. Here, he was obeying Ezra Pound’s asinine injunction, a century ago, to ‘Break it up! Break it up!’

We may think this crumbled prose, but the product is an authentic, paid-up, modern American poem, complete with an occasional grunt of disregard for ordinary punctuation. To remove this veneer of pretension certainly exposes the communicative fragility and argumentative poverty of the piece. How often is the main verb, that motor of the prose sentence, suppressed.

But, wait: we have not finished. There is another layer of varnish available to the poet, with a couple of flicks of his word-processor, by means of which he may strengthen his claims to be the right-on, modern American poet, a technique further redolent of The Cantos, that vast and popular[2] primer of illiteracy, the technique of indentation:

Now it even looks like a poem! In addition to completely arbitrary and superficial line-breaks, we now have a verse-array!

But I don’t want to be unduly negative about this still-born little slip of a poem. Let it be put back gently in the Museum of Literature whence it came and where it belongs. The point, surely, is that this poet hasn’t even begun to think about the form of the whole, the life that builds up from the line into the verse-paragraph, the suite or sequence, and the work as a whole. I doubt if metre-and-rhyme would improve matters (the mould improve the jelly?), although the extinction of the tedious autobiographical American poetic voice would be a relief (Whitman is the other unfortunate godfather of officially sanctioned American ignorance). On the other hand, the prose-poem is a perfectly valid, muscular yet stream-lined genre that has been too little exploited. Let all such poems be presented as prose. Their shortcomings will be exposed, but a natural weeding-out will leave the best standing beside those of Rimbaud and Baudelaire.

Let us have a little less lazy revolution and a little more dedicated apprenticeship.

[2] Pound hd invtd the txt msg half a century before the mobile phone.

[3] Philip Booth, from Lifelines: Selected Poems 1950-1999, Penguin Group, 1999.

January 19, 2010

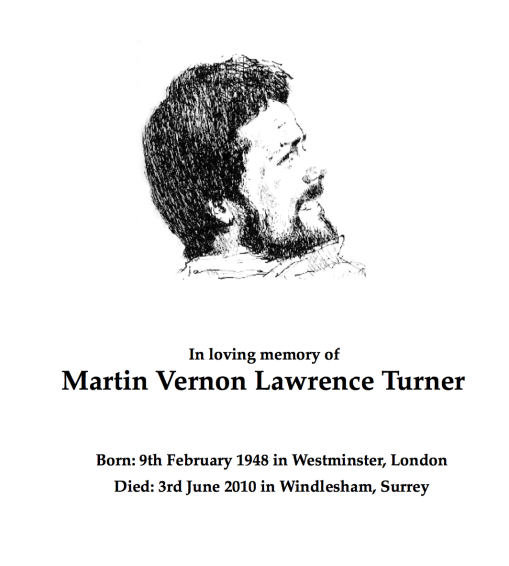

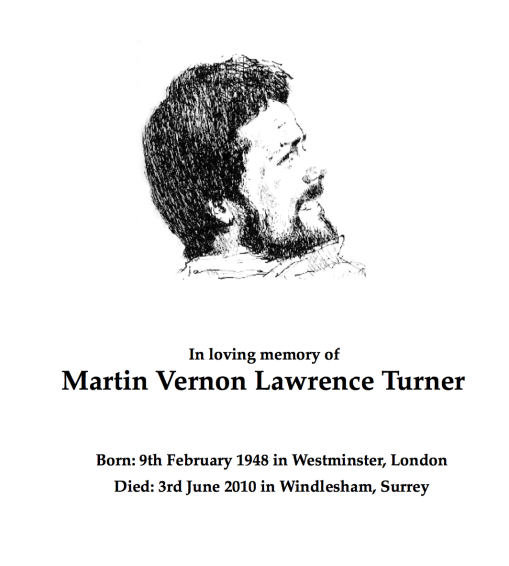

Martin Turner, who is on the Windmill Club’s committee, said: “It’s about making sure everyone has a bit of a laugh.”

Martin Turner, a spokesman for the Specialist Schools and Academies Trust (SSAT), organising the tour, praised the Chinese handling of the outbreak.

But after these three were dismissed, the middle and lower-order had little to offer except for 20 not out from Martin Turner, and the visitors were 139 for 9 after their 50 overs.

NHS Walsall spokesman Martin Turner said: “It is with sadness that we have to announce that a third person from the West Midlands who had tested positive for H1N1 swine flu has died. The death is under investigation.”

Visitors will also will hear Bible readings and worship songs and share Holy Communion, administered from the base of the plinth by Rev Martin Turner.

Camilla Parker-Bowles will be played by Joanna Van Gyseghem while Martin Turner will play Charles.

As the lead vocalist, bassist and principal song-writing force behind Argus, Martin Turner is delighted to be able to bring his creation to life once more.

But new research being carried out by Dr Martin Turner, a consultant at the John Radcliffe Hospital, Oxford, could help future sufferers by speeding diagnosis and improving drug treatment.

Just two weeks ago the Advertiser revealed that deputy head Margaret Southwood and assistant head Martin Turner were suspended amid allegations that attendance records were manipulated to boost the school’s rankings in league tables.

A police spokesman said Abigail Hancock and Sean Martin Turner of Langley Park, County Durham, disappeared after boarding a train in Durham at 4.23pm on Saturday.

Embedded among these various spaces is The Martin Turner Room … you can ask for this room at no extra cost and dine in splendid isolation among Martin Turner’s cartoons, which line the walls.

A mischievous mink caused eight hours of chaos when he sneaked into a busy city-centre store. Officers from the RSPCA … laid traps baited with food and turned off the lights to draw out the mink … Martin Turner … added: “Whatever happens to the little guy, at least he won’t end up as someone’s coat.”

Another former Shelford player, Shane Roberts, pulled the ball back for Martin Turner to extend their lead before Lee Dawson ran through to finish off a fine result.

When I met Riedel’s Martin Turner he was armed with four glasses to showcase four different types of wine … Turner poured a bit of mid-price Sancerre into it. “Now swirl it,” he said, and as I did so, it slopped dangerously at the edges. “Now smell it,” Turner instructed.

Rehearsals are well advanced for “Lend Me A Tenor”, a hilarious full-length farce, which producer Martin Turner says “will make ‘The Full Monty’ look like a Sunday school picnic.”

Seven Ledbury men are all set to have their hair, beards or moustaches shaved off to raise money for a special school … which caters for children with Severe, profound and multiple disabilities … [Among] the men taking part are … Martin Turner.

Martin Turner, the prospective Lib Dem parliamentary candidate for Stratford, accused the county’s fire and rescue service of producing a document that failed to use plain English.

Warning: Do not open this book to venture the streets of East London with jokester Martin Turner. Leader of the “Gang of Three,” Turner doesn’t care about anyone but himself … nor can he grasp how to use correct grammer and comprehensible sentence structure.

“It’s an interesting academic exercise to think what you should get,” says Martin Turner, a computer scientist specialising in fractal images at the University of Manchester, UK, “but it all depends on what properties you want to keep in the third dimension.”

This trio of boys from across the border are part of a growing number of Gold Coast teens turning their backs on their home town to celebrate their rite of passage in Byron. Eighteen-year-old … Brad Martin-Turner said they favoured Byron Bay because it was a holiday, not just a party.

The Hobbs’ problems multiply when Emily and Martin Turner stay the night. Emily, with her high-pitched, voice and Martin with his hair slicked back, bow tie and dark rimmed glasses, are a wacky couple.

Two of the cameras that comprise the EPIC instrument were designed and built at Leicester’s Space Research Centre by a team led by the late Martin Turner, one of the world’s leading experts in X-ray instrumentation.

The business was evacuated about 10:40 a.m. after a report of a robbery with an explosive device. Joseph Martin Turner, 47, of Orlando, was arrested the day of the incident.

Dr Martin Turner a Group Leader and Head of Babraham’s Laboratory of Lymphocyte Signalling and Development … said, “Studying how T cells develop helps us to understand healthy development, how T cells acquire specialised functions and what factors can cause lymphomas or other devastating illnesses.”

December 29, 2009

We spied down from our eyrie yesterday upon the small stage at the Comedy Theatre to see a starry cast exchange high calibre performances, albeit with a sense of cramp derived only in part from the frock-coat of Molière. The play was a modern re-creation by Martin Crimp of The Misanthrope, clever rather than moving, replete with 1990s references to Tom Stoppard being passé.

The dynamic of the original, in which Molière himself played Alceste, amid rumours of his emotional ricochets among his three actresses, lies not in the relationship ─ which seems to open (“You’re the only one here who understands me,” says Jennifer after briefly stunning everybody by her journalistic treachery) and close (“Let’s escape from all this hypocrisy, go away to the country and make babies,” responds Alceste). Rather, it hovers around Alceste as the sole figure of integrity in a brittle world of log-rolling, mutual back-scratching mediocrity which is universal and undoubtedly contemporary.

Because Molière was fighting entrenched, predatory interests ─ government, Catholic Church ─ with only the veiled and intermittent support of the Sun King, he had to have an escape route. This is achieved by not taking the part of the defiant Alceste but, instead, of the catty mob. It is thus expedient to paint Alceste as a pepperpot, a ‘misanthrope,’ rather than the clear-sighted satirist he, like Molière, actually is.

This production adheres closely to this disappointing failure of nerve, if to little else. Damian Lewis flings himself about sinuously but doesn’t abrogate the pepperpot rôle with any conviction. Tara Fitzgerald, released from her bespectacled, white-coated, focused, forensic boffin scenario in the entrails of Waking The Dead, several times electrified the whole theatre from her limited part. Keira Knightley, burdened throughout with the accent of an American movie star, carried off her more dramatically mobile rôle with angular, elegant panache. The stage managed to refresh itself ─ with music, with candlelight, with costume ─ from time to time, the actors emitted aplomb and the fireworks fizzed, but the latter were more verbal than dramatic.

December 27, 2009

It is sad to see Alexander Solzhenitsyn depart and worth casting an eye once more over this 20th-century writer of incomparably heroic stature.

Solzhenitsyn was both a great Russian novelist ― though no Tolstoy, Dostoevsky or Pasternak ― and more than this. Like Avvakum trekking the shores of Lake Baikal, he retained the mission of the prophet-purist and perhaps saw himself as a religious leader. Art and prophecy jostle in Russian literature. In the course of his fully-televised global re-emigration into the ferment of post-communist Russia (from Vermont via Vladivostok), he may have been disappointed to find Boris Yeltsin bobbing like a ping-pong ball on the fountain; but from my brief and indirect contacts with the distraught Mrs Yeltsin, I can only feel thankful that Solzhenitsyn was spared such undignified upheaval and consternation.

Given the ability of the KGB to reach out and murder Bulgarian dissidents (Markov) and Russian former agents (Litvinenko) on the streets of London, and contrive the murder even of a pope on the streets of Rome (John Paul II), it had been no fantasy that inspired Solzhenitsyn to create a fortress in Vermont from which he rarely emerged.

So what more was he? A historian and documentarist. A writer with the impudence to think that, as a calf tethered to a stout oak tree, he should at least keep butting away. How could he have known he would one day ultimately succeed, an individual who, more than any other, brought about the collapse (“through its own inner contradictions”) of an evil empire.[1]

It is remarkable to think that in 1951, in his luminously original and prescient The Captive Mind, Čzesław Miłosz should still have seemed to think that Marxist ideologists were immensely cunning, resourceful and intellectually triumphant, perhaps like Vatican theologians (though he does not say this). Yet in fact Marxist ideology was never like this. It was a self-justifying smokescreen behind which thieves and gangsters could go about their accustomed business robbing and killing the innocent.

Bear in mind, indeed, that the finest philosophical minds in Europe had identified the intellectual flaws in both Marxism and Freudianism by, roughly, the end of the First World War.[2] This, though (I digress for a moment), is an example of the wide and ever-widening gap between the elite and the mass of those left behind, many of whom will never catch up. (One has to remember that in the West half, and in the rest of the world perhaps three quarters, of the population has an IQ of 100 or below.) This is the problem I call the Tail of the Comet, symbolised today by the intellectual distance between the Large Hadron Collider and the increasingly headscarfed and monolithic streets of Cairo, Istanbul and Alexandria, formerly culturally diverse cities like Beirut. Perhaps the tragedy of September 11th 2001 best captures this gulf of centuries. It is a hallmark of the uneducated mind that it takes symbols literally.

Lenin, who invented the Gulag, understood perfectly the dis-equation between strength and weakness, a feature of Russian backwardness in Tsarist and Leninist times alike, then as now. Russia is a vast world with nonexistent or crumbling borders across which its forces flutter like chickens. The only border it understands is the Ice Sea.

Intriguingly, One Day In The Life Of Ivan Denisovich was not even original when it finally saw the light of day in 1962, in the shortlived Krushchev thaw after the death of Stalin.[3] Even before Solzhenitsyn had been arrested for a commonsensical remark in a letter to a friend seen by censors, Russians who had been unable to pronounce the name of a Pole captured in 1940, Gustav Herling, thought he must be a nephew of Hermann Göering and processed him into the Gulag. He survived two years by a chain of miracles to produce A World Apart in 1951. This remarkable documentary account retains, if possible, still more of the immediate vividness and knife-like moral edge of daily camp life. Ivan Denisovich, after all, has a good day. There is less optimism in Herling and he never returned to this theme.

There is little fine writing in Solzhenitsyn, though his analytic aim ― for instance in August 1914 and Lenin in Zurich was acute: a historian’s instinct. Most impressive are his networking efforts in relation to fellow zeks (convicts) whose testimony seemed to him to teeter on the verge of extinction. Compensatingly he therefore spared no effort to gather, through meetings and correspondence, every scrap of first-hand witness account he could lay his hands on and incorporate it all in the three mighty volumes of The Gulag Archipelago (I still haven’t read the third). No longer could a trivialising Sartre argue against the eyewitness testimony of the trickle of survivors arriving in post-war Paris, thus seriously compromising his relationship with Camus.[4]

Nothing could have done more to shake the oak tree and root world opinion in a more realistic view of the workers’ socialist paradise. Reagan, Thatcher and Gorbachev swayed in the upper reaches of the oak tree in thermals long before activated by Alexander Solzhenitsyn.

Martin Turner

18-Sep-2008

[2] For a readable account, see: Popper, K.R. Unended Quest: an intellectual autobiography. Glasgow: Collins (Flamingo), 1986. Nothing however was available to prevent Karl Marx from building on the foundations of the crab-like Hegelian dialectic ― Hegel’s deterministic philosophy of history ― after they had already been decisively exploded by Kierkegaard. And Marxist-Leninist and Freudian ideas have progressed blissfully ever since in western academic departments of literature and history.

[3] The subsequent film, starring Tom Courtenay, was banned from public viewing in Finland in 1970.

[4] Sartre actually became a perfectly orthodox Marxist at the end of his life.

December 23, 2009

The modern idea of modernism is already quite old, and traceable back at least to the middle of the 19th century. It has different meanings at different junctures. One period that interests me is the interlude between the two world wars. The atmosphere that followed the carnage of the First World War ─ and for a long time nobody knew that a Second was coming ─ was quite manic, perceived as festive at the time and as hysterical today. The gulch of modernism seemed to run like raving water, as DH Lawrence would say, between the steep and rocky walls of two world wars.

This is the context into which Lawrence’s The Captain’s Doll fits and it is a representative work of its time ─ it was first published in 1923 ─ as much so as the portraiture, literature and to some extent music of the day, of all of which it contains faithful echoes. But like all of the works of Lawrence it quickly establishes itself as timeless, concerning itself, as it does, with the relationship between a man and a woman over several years. In only 64 pages (in my edition[1]) it burrows with Lawrentian acuity to the heart of this relationship and worries away at it like a terrier.

Lawrence has the confidence of a man who has trained his reader. Each sentence is a live and sinewy creature, engaging on the one hand with the corpuscles and morsels of words themselves, and on the other introducing the very characteristic tattoo of Lawrentian repetition, a device which enables Lawrence to distribute emphases, and thus keep the reader’s attention, as he goes along. It is a unique instrument and contributes mightily to the impression that this man can compare favourably, if one were so childish as to want to do so, not only with the Bennetts, Hemingways, Fitzgeralds and Waughs of the period, but with the best writers of any and every age.

An example, not quite at random, will suffice here:

A thousand other sentences would have demonstrated the same thing. We have the music of steep loops upwards, the repetition and emphasis of upwards and the poise and musical delivery of the sentence as a whole in its acoustic envelope.

This describes a level of poetic control unusual in most novelists, but what really wakes up a reader within a few initial paragraphs of any DH Lawrence fiction is the expansion of intuitive intensity with which characters perceive each other and are described. As in an encounter group, we are led directly into the realm of what people truly think and feel about each other. This zone of truth is commonly approached much more gradually, if at all, in the work of more circumspect novelists, but Lawrence seldom seems to bother doing anything else. Like Jane Austen, he scarcely indulges in incidental description, preferring to let the reader know quickly what the essential territory is that interests him. There is little distinction between public and private.

In the poverty and reduced freedom of British-occupied post-First World War Germany, a doll-making Countess and her Baroness friend interact with a British Army captain, his wife come to check up on him from England and, briefly, a local German politician, beautifully drawn, who appears as a possible candidate husband for our Countess. I suppose we know from the comic melancholy of the latter that the serious business will always be between the Countess Hannele and Captain Alexander Hepburn, but Lawrence manages to obscure the highly ambiguous outcome up to and including the very final sentences of the story. Will they marry or won’t they? (The Captain’s wife has fallen from an upper window and died, a huge sacrificial benefit to the narrative.)

Most of the drama, when the Captain seeks out Hannele in Austria after an interval of years, follows the escalating upward ascent of mountains towards a solid glacier that sits in a little valley at the summit. Thus the twists and turns of the journey and the excitement of the scenery do duty for Lawrence’s unfolding of the remarkable dénouement, in which a marriage is apparently agreed.

But the essential question for a critic is, what exactly is Lawrence up to in this novella ─ what is the purpose that has brought the story about, what is the itch that drives the writer’s creative agitation? This, it seems to me, has to do with a desire to satirise the faint, bleating amours of the English upper classes. The common and characteristic verbal gambit of Alec is to respond, “Quite,” to the conversations of his wife or his lover. Lawrence has a very good ear for this sort of thing: he has not hung around the drawing-rooms of Bloomsbury and Garsington in vain for all that time, boiling inwardly no doubt, but catching perfectly the self-detaching accents that we hear today in the talk of Mrs Hepburn:

The countess is not presented as a complex character. Her moment comes, climbing the mountain, when she arrives at the aperçu that the stony and isolated Alexander wants her to love him. Indeed, the reader is unable, when all is over, to disagree much with this. But throughout the story Hannele’s astonished fascination with this man is emphasised. She doesn’t understand him, cannot read his emotions and finds the experience intriguing. To this extent, Hannele is the reflecting surface for the drastically limited, and possibly inhuman, emotional life of this crippled man who has never loved anybody, who now proposes a loveless marriage and who is incapable of rising to the existential occasion with any tone beyond that of take it or leave it:

Lawrence maintains to the end the drama and uncertainty of this exchange. It is only afterwards that the pieces settle into any kind of order. Earlier on, one is exposed to the thoughts and feelings of Alexander by the author himself, hovering and fluttering around his character; but in the later passages the Captain is described wholly from the outside ─ through his actions. This, then, may be the point: that not only are the British upper classes incomprehensible to foreigners, especially defeated Germans, but that any particular male member of them is, in precise and elaborated detail, so unalive, so defeated by life, as to be limited and stunted, and even beyond this radically incapable of normal relationships. It may be that all this is caricature, Lawrence’s alienated class consciousness seizing on the movements of the elite like an entomologist as others have done before and since, but it also seems pretty faithful to the clipped and etiolated moeurs of the period as one comes across them, for instance in the Diaries of Evelyn Waugh.

Fortunately, we English love to laugh at ourselves, though England is not what it was. Today we can welcome Lawrence’s astounding, riveting, versatile and fecund critique as a tour de force in the particular genre that he seems altogether to have invented.

[2] Op. cit., p. 498.

[3] Op. cit., p. 473.